Pathologist Katie Gold joined Cornell University last year to perform research and extension work in grape disease management. And though her position as assistant professor of grape pathology is not new, her approach to it is.

Gold’s experience with remote sensing, proximal sensing and hyperspectral imaging — the study of how light interacts with objects — makes her unique in the world of grape disease detection. Her research tools range from satellites in space to handheld devices at the vineyard level, and her focus on early disease development has the potential to revolutionize disease control in New York and beyond.

“Hyperspectral imaging, especially applied to plant diseases, is a new field,” said plant pathologist David Gadoury, a Cornell senior research associate. “It allows us to see things using wavelengths of light not visible to the human eye. It can find symptoms that would be missed even with the most intensive visual assessments.”

Gold’s new Grape Sensing, Pathology, and Extension Lab at Cornell (GrapeSPEC) studies the basic science of how light interacts with diseased plants and how to use that knowledge to improve vineyard disease management. The lab is based at Cornell AgriTech in Geneva, where Gold arrived in February 2020 after spending six months with NASA. She earned her doctorate in plant pathology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 2019, where she studied the use of hyperspectral sensors for presymptomatic disease detection in potatoes and other specialty crops.

“I describe myself as a reformed vegetable pathologist who worked at NASA,” she said with a laugh.

Gold joined Cornell five weeks before the university started implementing coronavirus-related lockdowns. Her team has been working remotely ever since, except when they’re in the vineyard.

“I can’t say I recommend launching a lab during a global pandemic, but I’m proud of what my group has done,” she said. “Our focus is to push forward the boundary of what’s possible with plant disease sensing, in order to create useful tools for growers.”

Her team conducts pathology trials on about 4 acres of vineyards in Geneva, where they study powdery mildew, downy mildew, botrytis, sour rot and other diseases.

One of the major problems with grape pathogens in New York is their unpredictability. The intensity of infestation varies from year to year. Powdery mildew, in particular, is “boom and bust” — it’s hard to tell how hard it will hit until it hits, Gadoury said. And by the time it hits, all growers can do is try to contain the damage. Hyperspectral imaging technology promises to warn growers if a disease is coming — at a point when they actually can do something to prevent it.

Gadoury said Gold is not just a cutting-edge technologist but a “good plant doctor.”

“She will not just bring new technology to the table, but will be a leader in getting it worked into disease management systems,” he said. “It’s not enough to just be a brilliant researcher. The best outcomes for growers result when a person who’s actually done the work can work it into their systems.”

NASA detour

When Cornell first approached Gold about her position, she was already contemplating a temporary appointment with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. Cornell agreed to sponsor a six-month joint appointment with JPL before she joined the university full time, she said.

At NASA, Gold and other researchers used hyperspectral imaging to do vineyard surveillance from satellites and aircraft, as well as from the ground. She is using that knowledge, and access to those resources, to bolster her pathology work in New York.

Gold said being part of the grape industry and the NASA community at the same time made for some surreal moments.

“I got a grower phone call standing 30 feet away from the Mars rover,” she said. “I loved that.”

Even more surreal, she learned that the only other Cornell faculty member to have a joint appointment with JPL was Carl Sagan.

Ryan Pavlick, a JPL research technologist, worked with Gold in California.

“The work Katie is doing is quite novel,” he said.

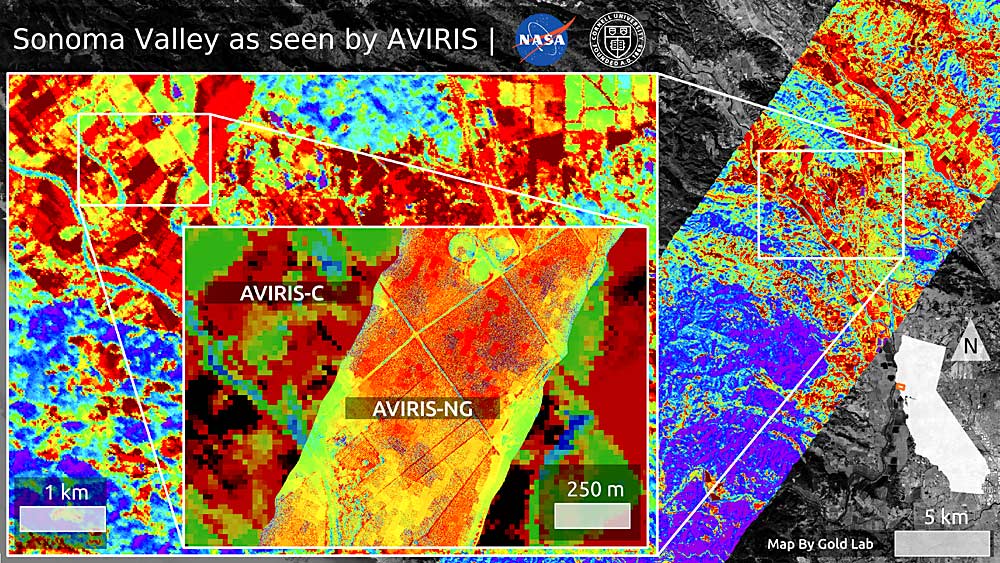

Pavlick and Gold used one of JPL’s AVIRIS (Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer) instruments, nestled in a plane, to make a hyperspectral map of California vineyards from the air. On the ground, a team led by Gold collected samples from the vineyards using handheld spectrometers, in order to validate the airborne sensor’s findings about how light interacts with grape leaves, Pavlick said.

The JPL aircraft work is restricted to California for now, but Gold hopes to expand it to New York one day. She’s also excited about the PhytoPatholoBot, a prototype autonomous vineyard robot developed at Cornell that’s capable of detecting downy mildew with 90 percent accuracy. These are just a couple of the cutting-edge tools growers will eventually be able to use to make better crop protection decisions, she said.

“I see myself in the business of information generation,” she said. “The grower makes the decisions.” •

—by Matt Milkovich

Leave A Comment