Since determining that the range of phylloxera infestation in Washington wine grape growing regions was greater than previously thought, recent research supported by the Washington wine industry is providing new knowledge about the pest in local conditions. For one, we’ve learned there are more areas within the state that have potential for phylloxera to take hold in a vineyard.

It’s long been believed that the light-textured and wind-blown soils common in Washington’s wine grape growing regions are a primary reason that the tiny, aphid-like insects haven’t devastated vineyards, especially considering most are planted with own-rooted Vitis vinifera varieties. Early research in France and California found that sandy soils are not conducive to sustaining phylloxera populations. Although phylloxera have been found sporadically in a handful of Washington locations for the past 100 years, the detections were usually in Concord vineyards where the pest doesn’t pose problems — not in susceptible Vitis vinifera.

The Washington State Wine Commission’s board of directors approved funding two years ago for a three-year research project focused on pest biology of phylloxera, pest management and education. The research team is led by Washington State University’s Doug Walsh, Michelle Moyer, Gwen Hoheisel and Markus Keller.

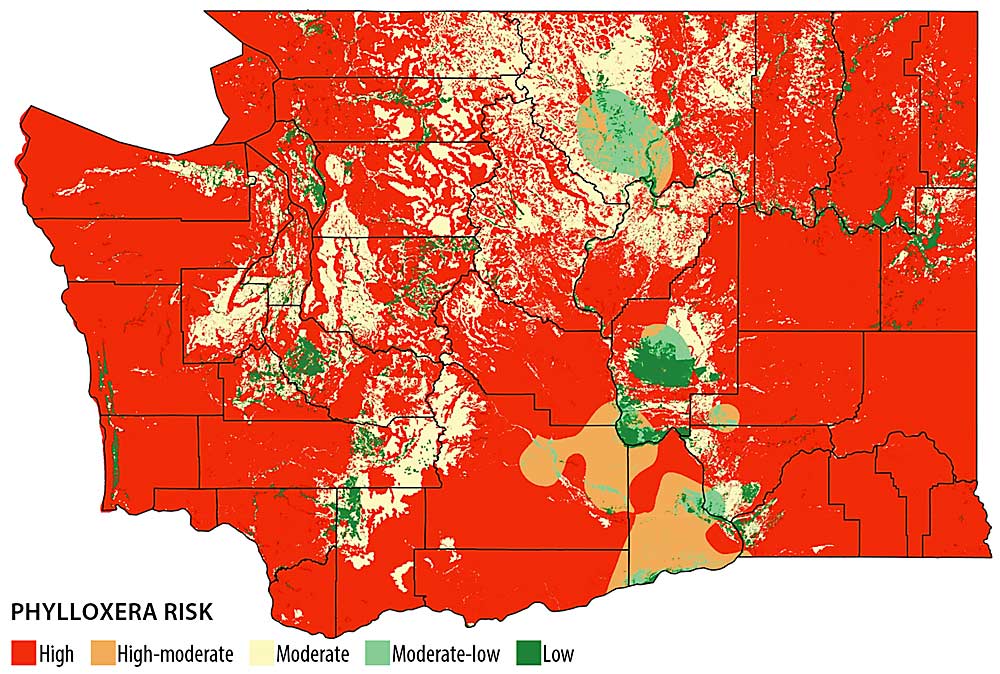

A top priority of the project was to determine the scope and severity of the phylloxera infestation in the state and develop a risk-assessment mapping tool to help growers identify vineyard locations with soils that could support phylloxera. The WSU team recently completed this objective and developed a phylloxera webpage that includes the risk assessment map and other valuable resources.

Mapping tool

The phylloxera risk assessment map, developed by Abhilash Chandel, Moyer, Keller, Lav Khot and Hoheisel, considers both soil texture (sand content) and soil temperature in assessing risk to a vineyard. Sand content greater than 80 percent is categorized as low risk; sand content less than 65 percent is considered high risk. Soil sand content is the most important risk factor for survival of phylloxera, but soil temperature can influence survival. Soil temperature used for the map is the average temperature at 8 inches deep between June and August (i.e., available soil temperatures through WSU’s AgWeatherNet weather station network). Soil temperatures below 65 degrees Fahrenheit or above 84 degrees are categorized as low risk; between 65 and 84 is considered high risk.

The map shows that much of Washington is in the moderate to high-risk category for phylloxera. Most soils are not sandy enough to discourage the pest from finding a home in Washington’s own-rooted vinifera vineyards: Not the news we had hoped for. The risk assessment map, with its red and orange colors depicting high to moderately high risk, illustrates that “my sandy soils will protect me from phylloxera” is wishful thinking for most growers.

The map gives an overview of soil textures because it was cost- and time-prohibitive to drill down for each vineyard location. If you have a vineyard in a moderate- to high-risk area, take a soil sample and evaluate it for sand content to inform your site-specific risk assessment. Site-specific soil temperature data, if available, can also further refine your risk assessment.

ONLINE: WSU’s Phylloxera Risk Assessment Map and other resources can be found at: wine.wsu.edu/extension/grapes-vineyards/grape-pests/phylloxera.

Risk doesn’t mean phylloxera is present

If your vineyard falls into the moderate- to high-risk category, WSU recommends sampling for the presence of phylloxera in areas where vines show signs of slow growth and development.

A high-risk vineyard doesn’t mean that it has phylloxera. But if the pest is introduced, there is a high risk that it can become established (i.e., survive) at the site, and once a population is established, it is likely to thrive. If you grow grapes in a location ranked moderate- to high-risk and you currently don’t have phylloxera, it is prudent to take steps to keep it that way:

—Follow state quarantine restrictions on out-of-state plant material.

—Consider using certified, bare-root planting materials for easier root inspection.

—Reduce the movement of soil within and between vineyard locations.

—Clean all equipment (cultivators, harvesters, ATVs, tractors, etc.) of soil prior to moving between locations.

Pest biology and management

WSU scientists funded with Washington wine industry dollars are also working to better understand phylloxera biology under the state’s conditions. Populations of phylloxera have been intensively monitored at vineyards near Walla Walla, Sunnyside and Zillah to learn about life stages and the number of generations per year. Walsh is investigating different methods to search for phylloxera, besides digging roots and looking for eggs. He is comparing using inverted bucket traps and two-sided sticky tape wrapped around trunks to capture the tiny pest during the summer and fall sampling periods. To date, the research team has trapped more than 1,000 phylloxera with the bucket traps and sticky tape. The sticky-tape method appears to be a more accurate method to monitor phylloxera at the study sites than the inverted bucket.

In addition, phylloxera populations from multiple vineyards have been collected for a DNA barcoding study that will take place later this year. The DNA barcoding will help quantify the number of phylloxera introductions in the state and their origin. Are the populations from new biotypes that were recently introduced into the state, or are they endemic and increasing their range? This information will help determine if populations have been here for years or are the result of a recent break in quarantine regulations.

Lastly, Walsh is conducting field efficacy insecticide trials with registered and experimental systemic and contact insecticides to learn if there are tools to slow the spread of phylloxera. He is also manipulating soil temperature with plastic mulch to learn if high soil temperatures impact phylloxera. Data from these trials are still under analysis. The goal is to learn if there are management tools that can buy growers time before the need to replant on rootstock.

Experiences from other wine regions show that rootstocks resistant to phylloxera are the only effective way to prevent vine decline. While current phylloxera research doesn’t address rootstocks, Washington’s wine industry began supporting a long-term nematode project in 2014, and it includes evaluating a variety of rootstocks (with phylloxera resistance) against own-rooted vinifera for nematode resistance and general viticultural performance under commercial field conditions.

Statewide rootstock trials would take too long, cost too much and still be unable to study all possible combinations of site, varietal, irrigation and management styles. Thus, Moyer assisted Inland Desert Nursery with a Western Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education producer grant, to help set up a rootstock demonstration trial at their Benton City nursery site. Grower field days will be held later this year.

Research will continue to be an integral part of addressing phylloxera in Washington vineyards. Through scientific discovery, we will help provide tools to move the industry past phylloxera and be ready for the next challenge.

—by Melissa Hansen

WAVEx webinar focuses on phylloxera

Washington wine grape growers are invited to learn about the latest phylloxera research findings during the WAVEx webinar scheduled April 20 at 3 p.m. Pacific Time.

Following new discovery of phylloxera in Washington state in 2019, a coordinated and comprehensive research project to learn about phylloxera was initiated in 2020 by Washington State University. The research, supported and funded by the Washington wine industry, is led by Doug Walsh, Michelle Moyer, Markus Keller and Gwen Hoheisel.

In this free webinar, Moyer will share how the risk map was developed and how to read the risk categories and utilize online phylloxera resources. Walsh will discuss preliminary results of his efficacy trials looking at contact and systemic insecticides for control. One pesticide recertification credit has been requested from Washington and Oregon agriculture departments. The webinar will allow time for questions from the audience.

Washington Advancements in Viticulture and Enology (WAVE) and WAVEx are a series of research seminars and webinars sponsored by the Washington State Wine Commission and WSU. WAVEx is the condensed, shorter webinar series. The events help make wine research findings more accessible to growers and wineries.

Register for the webinar here: washingtonwine.org/wave.

—M. Hansen

Leave A Comment