When it comes to calcium-related disorders, the challenge may be more about getting the calcium to where it counts in the fruit — and when — than simply about the nutrient supply.

That’s the takeaway from a three-year project led by Bernardita Sallato, a Washington State University tree fruit extension specialist in Prosser who set out to identify the limiting factors for calcium uptake and the ways to correct them.

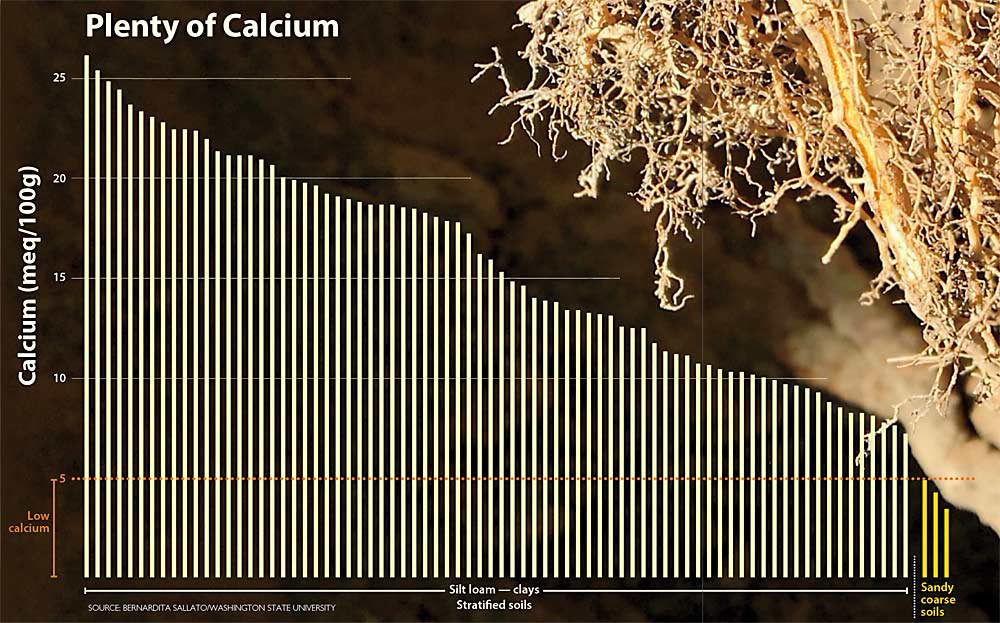

Like most calcium-related studies, the answers are varied and nuanced. But one thing is clear: A lack of calcium in the ground is not the problem.

Most Eastern Washington soils have plenty of calcium, a plant nutrient critical for preventing bitter pit in apples. Sallato collected soil samples from 127 sites around the state, visiting 79 of those personally. Only three fell short of recommended levels.

Feeding trees calcium through soil fertilizers or sprays often just throws money at the problem, Sallato said. (See: Calcium for bitter pit: Save it, don’t spray it.) The solution usually lies in pruning and irrigating to control vigor, careful crop load management and improving the physical characteristics of the soil, at least for Washington growers.

“We need to address the problem, not the symptom,” she said.

Her study, funded by a $153,000 Specialty Crop Block Grant, was the Chilean native’s first formal research project since arriving in Washington in 2016. Her results, however, line up with her pedigree in horticultural nutrition and decades of literature, she said.

The limiting factors she found — alkaline soils, high potassium and poor drainage — aren’t unexpected, and her recommendations for overcoming them are common practice.

Limiting factors

Calcium is a critical nutrient that helps keep cells together while fruit starts to form, especially during cell wall formation — up to five or six weeks after full bloom. After that, the tree has trouble with “uptake,” the process of moving the relatively immobile element from the soil through the roots to the fruit.

Based on her study, the following factors limit uptake in Washington:

—Soil temperature. Typically, air warms up before soil, which means trees bloom before roots begin to send out new, nutrient-wicking root tips, which happens at about 59 degrees Fahrenheit or warmer. Trees rely on reserves of calcium early in the season.

—Soil acidity. Roots like a pH between 5.0 and 7.5. If higher than that, nutrients and important metals are tied up in the soil. Of Sallato’s Eastern Washington soil samples, 42 percent had a pH higher than 7.5 and 16 percent were over 8.0.

—Potassium. Unfortunately, Washington soils also have a lot of potassium, another necessary plant nutrient that is more mobile than calcium. Excessive potassium competes with calcium in the root zone and in fruit. Only 7 percent of the soils Sallato sampled were low in potassium, while 67 percent had excessive levels.

—Phosphorus. Though phosphorus, another critical nutrient, doesn’t compete with calcium, it’s commonly high in soils that are also high in potassium. That indicates other problems, such as insufficient drainage. Forty percent of soils sampled had a deficiency in phoswphorus.

Only 11 percent of the soils Sallato sampled fell within recommended ranges for all three elements — calcium, phosphorus and potassium.

What to do

Sallato advocates managing soil and controlling tree vigor.

She recommends breaking up caliche, veins of hardened calcium carbonate common in the arid Western U.S., and improving drainage. “That’s probably my No. 1 recommendation,” she said.

Also, when pH is above 7.5, she suggests acidifying soil. Use sulfur burners if you have a reservoir.

Mind overall calcium and potassium values, not just their ratios. Growers commonly ask Sallato for a recommended ratio. She balks, because even soils within an ideal ratio can have excessive amounts that lead to bitter pit, the same way that eating excessive amounts of the correct ratio of protein and carbohydrates will make you fat.

Sallato recommends waiting until after bloom to roll out reflective fabric, which keeps soil cool.

Consider root pruning, she said. Growers have successfully used the technique on vigorous rootstocks to reduce vigor and stimulate root tip growth. However, researchers are still deciphering how this affects late-season vigor.

For tree vigor, plant with dwarfing roots, prune in the summer, use plant growth regulators, manage crop load and control irrigation.

In fact, connecting more dots between vigor and calcium uptake is part of her next three-year project, recently funded with $42,000 from the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission. Starting this year, in orchards known for high vigor, she plans to treat Honeycrisp and WA 38 trees with plant growth regulators, summer pruning and maybe some root pruning to compare the treatments’ effects on calcium-related disorders.

Honeycrisp is well known for bitter pit susceptibility. WA 38, the WSU Honeycrisp heir marketed as Cosmic Crisp, sometimes develops a condition known as green spot, which Sallato suspects is related to bitter pit and similarly tied to a calcium imbalance.

In the end, she hopes to convey recommendations for how to manage calcium-related disorders, not find a magic wand to eliminate it. Some growers are frustrated by that approach.

“Many growers say, ‘There’s been 80 years of research and we still haven’t solved the problem,’” she said.

Shawn Tweedy, field operations manager for Chiawana Orchards, said the idea of a magic bullet solution is unrealistic. Every new study about calcium and bitter pit tells the industry that the issue is complex and multifaceted.

“This idea or expectation from a grower that complicated issues can be boiled down to a point-source solution … I think that’s a fallacy,” said Tweedy, a former water-quality chemist at the Hanford nuclear reservation near Richland, Washington. But researchers should respect the difficulties growers face in executing complex solutions, he said.

So far, studies have shown that balancing nutrition, vigor and crop load is the best way to prevent bitter pit, said Rob Blakey, research and development manager at Stemilt Growers in Wenatchee. Easier said than done, of course.

Bitter pit may have been noticed for decades, but the most susceptible apple, the Honeycrisp, has taken off in Washington only in the past 20 years or so. Even good growers can get bitter pit in Honeycrisps, he said. The region still has Honeycrisp trees reaching maturity and, therefore, balance.

“The more prosaic growers have realized that this balance takes time and are figuring out how to get balanced trees as quickly as possible,” Blakey said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Nice informations.