For today’s commercial storage operators, it might be difficult to imagine having to store apples long term without the ability to use 1-MCP. Just over two decades ago, the function of 1-MCP was discovered, and funding by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission expedited the transfer of knowledge into practical application.

The discovery process

Research that culminated in the discovery of the function of 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) began in the 1980s in the lab of E.C. Sisler at North Carolina State University. Sisler’s objective was to understand how plants detect ethylene, and one of the research strategies was to find chemicals that prevented plant tissues from responding to ethylene.

Work in the U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service lab in Wenatchee, Washington, began in the mid-1990s with apples. We followed up on some of this ethylene inhibitor work to understand the role of ethylene in promoting fruit aroma production during ripening, using several compounds Sisler’s work had identified as ethylene activity blockers but that had no commercial potential due to toxicity.

One of these compounds, diazocyclopentadiene (DACP), worked well as an apple fruit ethylene inhibitor, and fruit exposed to DACP had a marked reduction in production of ripening-related aroma. DACP turned out to work as an ethylene action blocker, releasing 1-MCP as it degrades, a process identified by Sisler and Sylvia Blankenship. Their recognition of 1-MCP as the active compound blocking ethylene activity led to a patent and subsequent availability as a commercial product for use on ornamental plants and flowers.

USDA-ARS in Wenatchee gets involved

Our work with apples utilizing this product began with our first experiment in March 1997, using Fuji apples previously stored in controlled atmosphere (CA). Even though the fruit had been in storage for months, effects on fruit ripening were apparent and this work led to work with many apple varieties in the 1998 season. The most striking result from that initial year of research was the complete prevention of superficial scald on Granny Smith apples, a result we had not anticipated.

In subsequent years, we continued variety tests and other work to examine: application rate, application duration, temperature during treatment effects, impact of air or CA storage, and duration of treatment effects. This research, funded by the Tree Fruit Research Commission, identified many positive effects on fruit quality, particularly firmness retention and physiological disorders, in addition to scald control. We also noticed some concerns, including a prolonged sensitivity to carbon dioxide for sensitive varieties such as Braeburn and Fuji. Identification of CO2sensitivity and other issues led to work to characterize how to optimize use of 1-MCP while minimizing risk of enhanced disorder development.

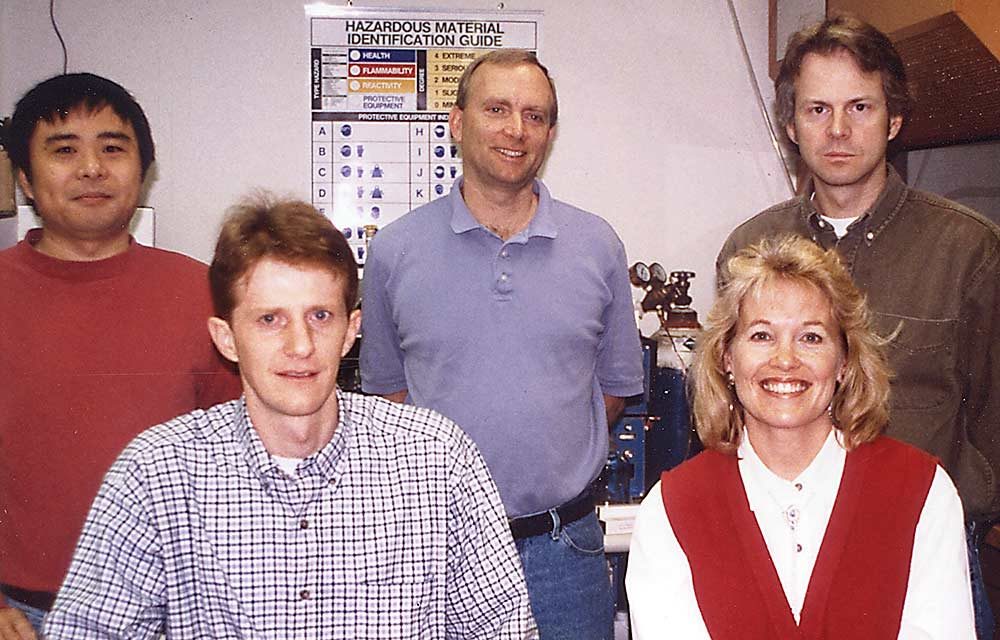

In addition to 21 apple varieties, we have characterized 1-MCP responses of a number of other fruit, including pear (10 varieties), apricot, banana, mango, nectarine, peach and sweet cherry, as well as several vegetables, including broccoli, carrot, green pepper and lettuce. The knowledge, dedication and commitment of the team that started this work, researchers Xuetong Fan and Luiz Argenta, and USDA-ARS lab technicians Dave Buchanan and Janie Countryman, was essential to the success of our lab’s research.

Research funded by the Tree Fruit Research Commission played a central role in 1-MCP commercialization decisions by the Rohm and Haas Co. After commercialization, our lab was supported by Rohm and Haas Co. for several years, to continue to explore the intricacies of 1-MCP responses in apple and pear fruit. Even now, nearly 20 years after 1-MCP entered the commercial market as a postharvest fruit management tool, we continue to explore how it fits with other aspects of postharvest management of apple and pear.

—by Jim Mattheis

Jim Mattheis is the research leader of the physiology and pathology of tree fruits research program at the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service lab in Wenatchee, Washington.

WTFRC and 1-MCP research

Between 1997 and 2018, the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission has funded 28 projects on 1-MCP led by 25 scientists from six universities and 16 other organizations. A total of $2.2 million was invested in research; $1.4 million for apple-related projects and $842,000 investigating pear-related subjects.

The USDA-ARS Wenatchee, under the leadership of Jim Mattheis, received the bulk of the funding.

The successful implementation of 1-MCP has enabled a year-round supply of apples, which translates into a 30-percent efficiency increase. It has expanded the potential to deliver premium quality fruit in hard-to-reach markets and has enhanced the marketing control of packed fruit inventory, since fruit can be stored longer before shipment.

Scientists use 1-MCP as a tool to understand physiological processes and in metabolomic and genomic experiments to uncouple the ripening response from other processes such as stress or aging.

—Ines Hanrahan, WTFRC executive director

Leave A Comment