This is not your grandfather’s X disease.

That’s one of the new findings scientists shared during the little cherry disease session on the final morning of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting in Wenatchee on Dec. 7. As session moderator Garret Bishop of G.S. Long said, little cherry disease is an umbrella term for similar symptoms caused by two different types of pathogens. Most of the talks focused on X disease, caused by the X phytoplasma, because it’s the primary pathogen of concern today.

But the phytoplasma today isn’t behaving like it did in previous outbreaks in the 1950s and 1970s, said Washington State University pathologist Scott Harper. Recent genetic testing confirms why: Two new strains have emerged, and they appear to be spreading faster.

The new strains, 2 and 3, “are harmful in the way that matters; they cause small, pale, immature fruit,” Harper said. They don’t show leaf symptoms the way the older strain, which is still prevalent in other regions, did, but they have more host plants.

“They can infect over 70 different species, so far. The list keeps growing every season,” he said.

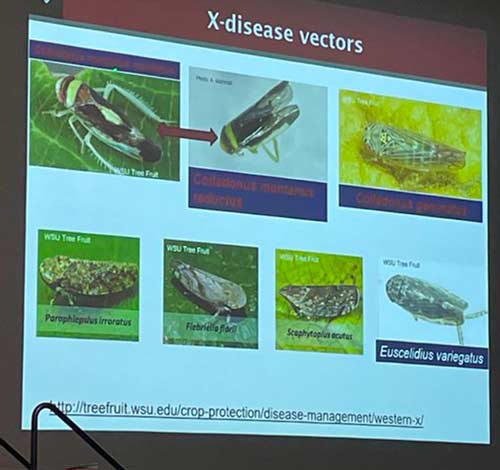

The management relationship between the orchard floor weeds that host the pathogen, such as dandelion and clover, and the leafhopper vectors that spread it is the subject of many current research efforts. Entomologist Adrian Marshall of WSU shared updates on those projects, including deterrence strategies to keep leafhoppers out of the orchard and how to interrupt the transmission cycle.

“Really, what we are concerned about are the nymphs. If an adult picks it up, it’s not going to live long enough to transmit it,” he said.

Removing infected trees is the most important strategy, as leafhoppers are only a concern if they are picking up the pathogen. The need to control weeds adds more complexity, Marshall said, and WSU is looking at herbicide strategies that could play a role in an integrated pest management program.

One bright spot is recent detection of some native leafhopper parasites and a recent trial of a fungal product, Beauveria bassiana, that can be applied to cherry groundcover to kill leafhoppers. “It seems very promising, and we will keep testing it,” he said.

Lastly, a panel of growers shared their experiences battling X disease — or keeping it at bay.

They stressed training everyone in your orchard to spot symptoms in the week or two before harvest, in addition to intentional scouting.

“Having the whole crew up-to-date on what to look for is a huge improvement,” said Teah Smith of Zirkle Fruit.

As for timing of pesticide sprays after harvest, when the leafhoppers are the most active and the transmission risk is highest, Smith recommended trapping and Phil Doornink recommended also watching your neighbors’ activities that can stir up leafhopper movement.

“If my neighbors are mowing, my border traps will start picking them up,” said Doornink, a Wapato-area grower.

All the panelists urged growers to remove symptomatic trees as soon as possible, but they differed on whether to replace those gaps in following years. Smith does, and so does Hannah Walters of Stemilt, along with fresh soil, but Jason Matson of Matson Fruit does not.

“Whenever we put in replants, we don’t seem to do as good of a job taking care of them,” he said. “They don’t get the same TLC as a new block.”

When it comes to planting a new block, Matson said he looks at the risk of disease pressure in the area around the block. One recent cherry removal was planted back in apples.

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment