What does “soil health” really mean?

Five years ago, Washington State University researchers launched a project to build a better understanding of that agricultural buzz phrase for Pacific Northwest orchards, specifically.

They found that the answer is, well, complicated. That’s because the role of soil is complicated, providing many different functions in the orchard system.

“We want healthy roots, we want water entry and movement, we want high water-holding capacity as well as soil fertility,” said Tianna DuPont, WSU extension specialist who led the soil health project with physiologist Lee Kalcsits. “There’s lots of things we can measure, but what matters in orchards? What’s related to our bottom line of yield and packout?”

DuPont said growers want to know which soil health indicators are limiting their production: It might be water-holding capacity in a sandy site, parasitic nematode pressure in a replant site, or even compaction preventing deep root growth.

DuPont likens it to how a barrel, with each of the staves at different heights, will leak from the lowest stave. It’s a common paradigm for thinking about how plant growth is dictated not by the total resources available, but by the scarcest resource — a concept known as Liebig’s barrel, named after the German botanist who popularized the idea.

As science’s understanding of soil health has become more complex, so has the metaphorical barrel, so that it now considers physical and biological factors along with the traditional nutrient ones, DuPont said in a webinar workshop about soil health held by WSU late last year.

To understand the common limiting factors for Washington orchards, DuPont and Kalcsits set about finding similar orchard sites with productivity differences so they could focus on the role soil health plays in the puzzle. Finding such paired sets for study was trickier than they initially expected, DuPont said. But they ended up with 60 sites they could pair and compare — with matching scion, rootstock, tree age and general location — out of 100 total sites they sampled.

Of those sampled, most sites had macro- and micronutrients well at hand, DuPont said, since the idea was to find sites where growers had challenges they couldn’t explain with fertility.

The common limiting factors were water-holding or compaction problems, as well as pressure from plant parasitic nematodes and root rot pathogens. The study looked at 21 metrics, including water-holding capacity, infiltration, root pathogen pressure, compaction, organic matter and microbial nitrogen availability — in addition to soil pH and macro- and micronutrients.

For example, one grower had two similar Gala blocks, but one was producing 60 bins to the acre and the other only 40. To determine if plant parasitic nematodes and root rot pathogens played a role, DuPont and her technicians collected soil from the orchard and pasteurized half of it. Then, they grew bean plants in the soil to see how much of a benefit the pasteurization provided. A big difference would indicate the nematode and pathogen pressure is impacting production.

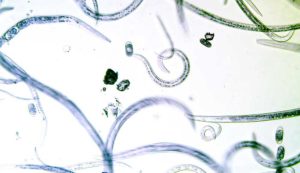

DuPont also counted the nematodes present in soil samples, using a sieving and settling technique designed to separate the microscopic worms from the soil.

“About 15 out of the 100 sites had more than 80 nematodes per 100 grams of soil, which is the threshold for damage to young trees,” she said during the webinar. “That’s 147 million lesion nematodes per acre, so that’s going to impact your roots.”

Another 15 sites had water-capacity concerns, usually on very sandy soils, and about a quarter of all the orchard sites had some compaction issues in the lower layers of soil, which did seem to contribute to some of the yield differences, compared to sites without compaction.

“These factors are all correlated, so we can’t just look at a single factor alone,” DuPont said. The model she and Kalcsits developed with the study data can account for the cumulative impact of the factors and evaluate which are most important for future assessments.

Interestingly, organic matter, which many studies link to soil health, didn’t correlate with orchard yields, DuPont said. Neither did soil respiration, which estimates the total level of microbial activity in the soil.

“The next step of the project is to work with soil labs to encourage them to include some of the important soil health indicators in their testing options,” she said.

One leading testing lab, the Cornell Soil Health Laboratory, already offers tests such as active carbon (a measure of organic matter), total available nitrogen, available water capacity and soil respiration. Director Bob Schindelbeck said they don’t conduct many tests for tree fruit growers, except for preplant situations.

Schindelbeck always recommends growers test before planting a farm, orchard or vineyard. “You can do your groundwork ahead of time because it’s easier to manipulate,” he said.

Most of the research into soil health metrics so far have been driven by annual cropping systems, he said, so research like WSU’s is needed to understand how best to assess and improve soil health in permanent crop systems. In general, the permaculture of perennial systems leads to better soil health, by many metrics, compared to that of annual crops.

“For perennial crop systems, the soil health is good, but the problem is the pests because they are sitting ducks, because you don’t have that rotation,” Schindelbeck said.

Compaction stands as another common problem he sees in orchards. Soils need plenty of pore space for air and water. He recommends testing with a penetrometer (New York growers can rent one from the Cornell lab, and they’ll help to analyze the results). He also said the lab is working on a bulk density test to assess if dense, tight soil could be limiting root growth.

DuPont said penetrometer readings over 300 pounds per square inch indicate root growth may be restricted.

In extreme cases, growers may want to mechanically loosen the soil with a deep ripping tool, followed by planting cover crops that send deep roots into the newly loosened soil, Schindelbeck said. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment