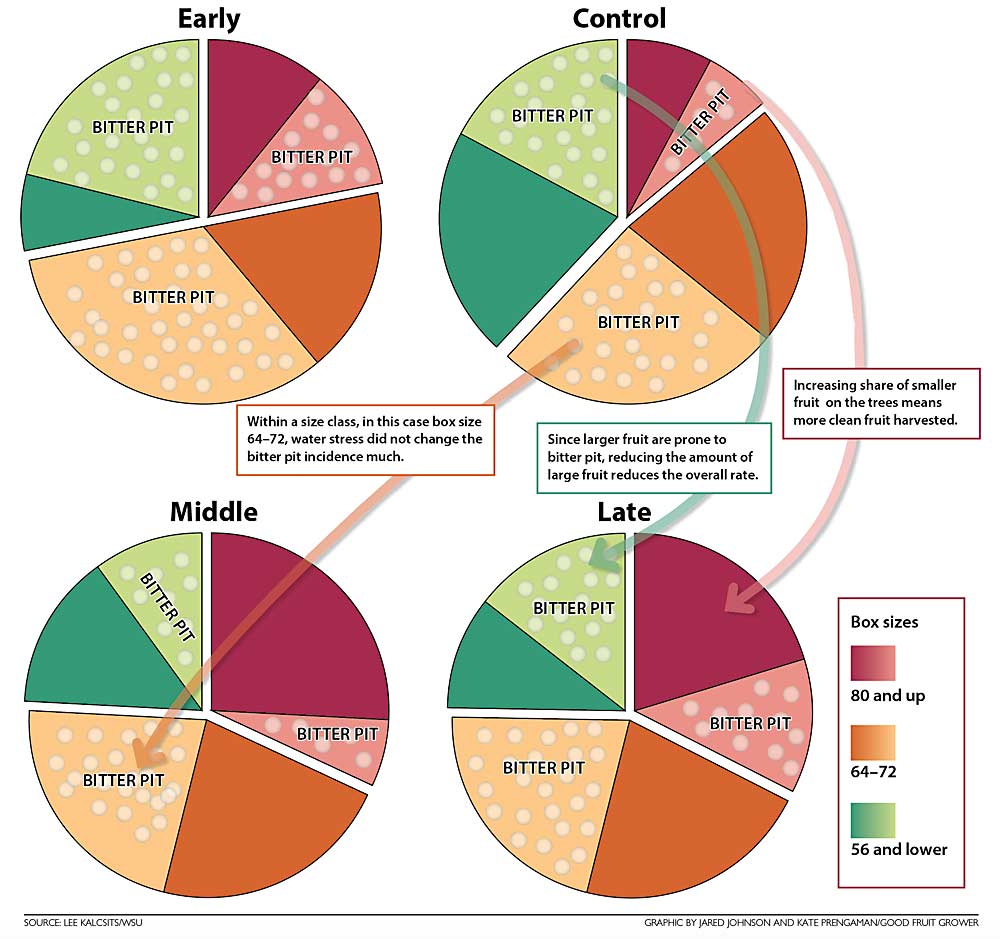

Honeycrisp growers already know that larger fruit are more likely to develop bitter pit.

That’s why Washington State University physiologist Lee Kalcsits wanted to see if using deficit irrigation to reduce fruit size could control bitter pit. In a three-year trial funded by the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, he found that both middle-summer and late-summer water limitations worked to reduce fruit size and bitter pit.

“If you had an orchard entering production and you produce 56s, you are pretty much guaranteed to have bitter pit,” Kalcsits said. “By shifting the proportion of fruit going into each size category, we are able to reduce the bitter pit effects.”

In a trial set up in a young Honeycrisp block at WSU’s Sunrise Orchard, irrigation deficits were applied during one of three monthlong periods: mid-May to mid-June; mid-June to mid-July; or mid-July to mid-August.

The early-season water deficit didn’t work. But middle- and late-summer deficits resulted in more fruit falling into smaller size classes, which have lower bitter pit incidence. They avoided water stress near harvest out of concern it could induce storage disorders.

“We drew it down to nearly 40 percent of field capacity during this period,” Kalcsits said. “Then, we’d water in small amounts to keep it from reaching a level of stress that could damage long-term health.”

To track stress, he and master’s degree student Michelle Reid used a pressure bomb to measure midday stem water potential. Of course, heat and sun exacerbate water stress, so it’s not surprising that the response to the deficit was less pronounced in the cooler 2018 season. Bitter pit incidence also declined as the trees matured from their third leaf to their fifth.

But despite those year-to-year differences, the relationship between size classes and bitter pit incidence is clear, Kalcsits said. It makes sense on a cellular level. Compared to other apples, Honeycrisp tends to have larger cell sizes, according to high-resolution scans of the fruit tissue. That seems to play a role in why it is more susceptible to cell wall breakdown that occurs in bitter pit development.

“The idea is that if we can reduce the cell size, we can increase the cell integrity to decrease bitter pit,” he said. “Eliminating water during cell expansion is where we can have that effect at a point where the cells are becoming larger, increasing the density of the fruit and reducing bitter pit.”

Growers try it

Kalcsits also worked with 10 grower cooperators to try deficit irrigation on their own terms. Each one did it a little bit differently, in terms of how they managed irrigation, but they all aimed for a month or more of moderate summer water stress.

Seven of the 10 participating growers successfully brought bitter pit below 10 percent with the deficit approach. For the other three, Kalcsits found nutrient imbalances: too much potassium out-competing the calcium that’s critical to fruit cell wall stability.

“If you have an imbalance, if you increase the density of your fruit, it’s not going to change that imbalance,” he said.

Most of the growers applied more moderate deficits than Kalcsits used in his research block – about 50 to 60 percent of usual irrigation.

“The research he’s doing is hugely valuable so I’m trying to mimic what he’s doing,” said Tim Welsh of Columbia Fruit Packers. He’s tried it on two blocks so far — not enough to make firm conclusions. “My only advice is to walk before you run. We need to be careful about not going too far too fast.”

The amount of water stress needed will vary depending on soil, orchard age and other management factors, Kalcsits said. An older orchard with deep roots might not get enough stress out of a 30-day deficit, while that would be plenty for a young block just entering production.

In order to apply just the right amount of water stress to reduce fruit size but not trigger negative impacts, growers will need some sort of monitoring system for soil moisture or, even better, stem water potential, which measures the stress the tree is experiencing, Kalcsits said. Honeycrisp trees don’t show water stress symptoms until they are pretty far into the stress spectrum.

“You cannot just do it by eye or feel,” he said. “You can’t make decisions off of whether the leaves are starting to wilt or whether you’ve watered lately.”

Plenty of irrigation service providers offer sensors and services to help. It may sound expensive, but especially in more uniform soils, the cost per acre isn’t that high. Kalcsits recommends starting in one block and building expertise before expanding the approach.

Welsh said he used neutron probes, a type of soil moisture sensor, in his fields and he’s interested in trialing some additional technology this year to see if he can more accurately assess the tree water stress. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Related:

—High-res Honeycrisp

—Growers try fighting vigor with water

Leave A Comment