Efficiencies designed to conserve irrigation water may in fact increase water consumption and leave some users with less water, a Washington State University (WSU) agricultural economist believes.

In Washington State, water is allocated according to a prior appropriations system, which means that a water right is set forever at a certain amount. Senior water rights–those set first–take precedence over junior rights.

Although this system has been criticized as being inflexible in terms of new water users, it is the best system for stabilizing water delivery, WSU economist Dr. Ray Huffaker explained at a recent meeting of the Washington Tree Fruit Industry Task Force.

“It protects senior water users from encroachment by junior water users and protects junior water users from expansions from senior users beyond their first appropriation,” he explained. “The purpose of the prior appropriations system is to protect all water users.”

But Huffaker said a bill introduced in the Washington State legislature this session, which legalizes water transfers, could allow some irrigators to use more water at the expense of others. Studies have shown that when irrigators use water more efficiently and are allowed to use the water “saved,” it may lead to greater consumption and a decrease in return flows to the stream, which may adversely impact in-stream flows and downstream water users.

Some irrigation systems are very inefficient. For example, the efficiency of a gravity flow system can be as low as 25%, while a sprinkler system might be 80% efficient. Water diverted for irrigation that is not consumed by the crop often returns to the stream or to an aquifer. By using more efficient systems, farmers can divert less water to irrigate their crops, and appear to be saving water.

However, return flows are also reduced because the farmer is not applying much more water than the crop consumes. “Diversion is less, but return flows to the river or to aquifers are also lower. You redistributed water, but you did not save any water,” Huffaker explained.

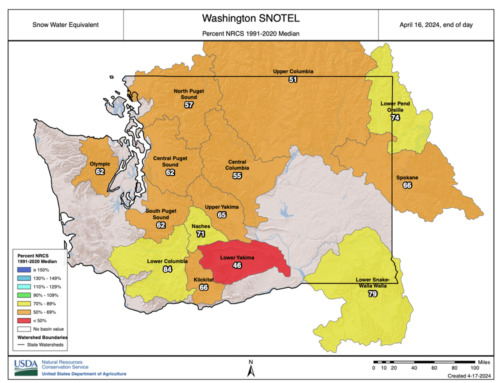

Representative Gary Chandler drafted House Bill 1113 in response to water shortages, particularly in the Yakima Basin, where orchardists with junior water rights have been seriously short of water in drought years.

He introduced similar legislation a year ago, but it was not passed by the Senate. Huffaker said.the bill raises some problems that people need to be aware of, and one of the most important ones is the fact that when an irrigator increases his or her irrigation efficiency, that may or may not be creating any surplus water.

“The bill seems to overlook that possibility and jumps right to the next step, which is allocating it,” he said. “If you’re allocating it, and it really isn’t a surplus, you’re allowing an upstream user to use a downstream user’s irrigation right.”

Huffaker said it has been estimated that 63% of the water in the Snake River comes from irrigation return flows, and overall in the West, 40% of the water in rivers are irrigation return flows.

Huffaker said.he is concerned that the state of Oregon has defined conserved water as the difference in diversions before and after efficiencies have been made, and it looks as if Washington will do likewise. He explained how such a definition can lead to problems, particularly in drought years.

If farmers use inefficient systems, senior users receive their allocations, but junior users in a district do not get their full amounts when there are shortages of water. With more efficient systems, senior users divert less, leaving more water for junior users, so that they all get their allotments. But basin outflows are decreased.

“Is that water conservation?” Huffaker asked. “While it’s water conservation in the eyes of the junior water users, it would not be considered water conservation if you were an irrigator in the next basin down. It’s quite an increase in use at a time when you thought you were conserving water.”

Huffaker said he hoped Washington would follow California’s example in defining water conservation as a reduction in consumptive use, rather than a reduction in diversions. Water conservation and transfers can work well in a system where excess water does not return to the river in any event, he said. In those cases, increasing irrigation efficiency actually does conserve water, and there is no harm in using the water saved.

But in general, in the West, return flows are important, he reiterated. “That’s why we worry so much about third party impacts from water transfers.”

He said if Washington irrigators go ahead and increase their irrigation efficiency and argue that the difference between what they diverted before and what they’re using now should be theirs to spend, it will be interesting to see how soon the downstream users who depend on return flows feel the impact.

Dr. Peter Goldmark, an Okanogan, Washington, rancher and a member of WSU’s Board of Regents, who was at the Task Force meeting, noted that people consider the water that they withdraw from the river as their personal property.

Even if they increase the efficiency of their system, they believe they have a right to determine what they do with the water they’re entitled to. Huffaker acknowledged that, but pointed out that the person down the river then has their rights interfered with.

“If you increase your consumptive use, it’s taking water away from someone else. It encroaches on other users’ water rights.” He said.a positive impact of increasing irrigation efficiency is that it enhances water quality by leaving more water in the river. ”

If your goal is water quality, and you’re decreasing throughout and leaving more water in the stream, you’re enhancing water quality, and that’s good,” he said.

Huffaker said hydrologists agree with his theory, and WSU would like to do a study to verify it, but it is difficult to prove. Measuring return flows–even if it could be done–would be very costly, he said.

Fred Valentine, chair of the Task Force, said.the key to making sure there is enough water for all the demands is to increase storage to capture water that is lost in the spring when it flows out to the ocean.

Mel Wagner, chief executive officer of the Yakima River Watershed Council, said.the reservoir system that supplies the watershed was designed in 1905 and completed in 1931.

It was designed to irrigate 600,000 acres, but only supplies water for 445,000 acres. He said.the problems are not being driven by irrigators’ water needs, but by the need to maintain in-stream flows for fish, which was not foreseen when the system was built. “The problem is being exacerbated by problems we didn’t used to have.” he said.

Leave A Comment