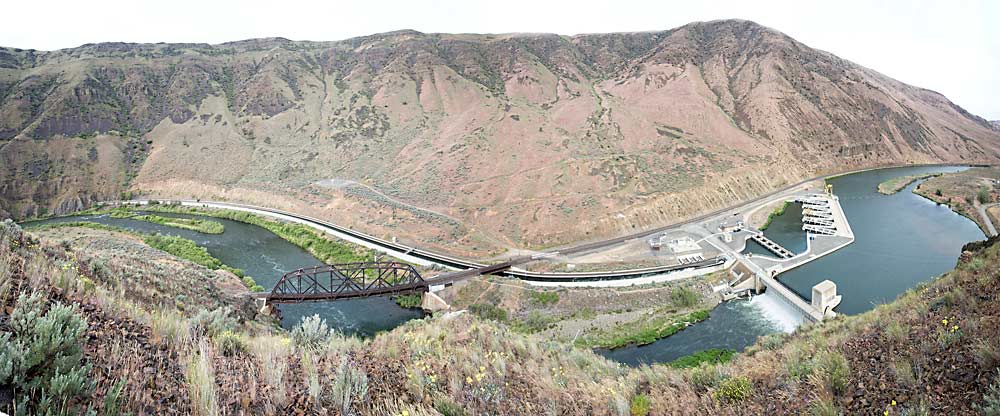

The Yakima River, as seen here overlooking Washington’s Roza Dam, delivers water to one of the top tree fruit production regions in the country, but it’s also home to salmon runs that the state and American Indian tribes are working to rebuild. Improving the water system for both farms and fish is a challenge, but Congress took a major step forward in February, authorizing the first phase of a 30-year, multibillion-dollar effort known as the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

In a rare show of bipartisanship, Congress has approved a broad package of public land projects that includes authorization for water supply and fisheries improvements in Washington’s Yakima Basin, one of the most productive specialty crop production regions in the country.

Once signed into law, as expected at press time, growers within the region who now have water rights subject to rationing in drought years will be able to invest their own money into a system to pump additional water out of one of the Bureau of Reclamation-run reservoirs during droughts.

“The goal is getting to a 70-percent supply for prorated water users and, at the same time, making things better for fish and wildlife,” said Urban Eberhart, manager of the Kittitas Reclamation District and advocate for the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan for water management.

The bill, passed by Congress in February, comes on the heels of the America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018, another behemoth bill with bipartisan backing that authorized $6 billion in investments for projects including reservoirs, harbors, flood control, drinking water systems and irrigation efficiency projects in the Klamath Basin in Southern Oregon and Northern California, another important agricultural region where limited water resources have caused tension between growers, fisheries, tribes and environmental groups.

Federally built irrigation infrastructure fostered Western agriculture, but in recent years, modernization efforts met gridlock in Congress, and litigation. The recent bills provide just a down payment on the major water infrastructure needs nationwide, according to the National Water Resources Association.

“It’s good to see that Congress has recognized that water infrastructure needed additional funding,” said Tom Myrum, executive director of the Washington State Water Resources Association. Congress also significantly boosted the Bureau of Reclamation’s budget for various projects this biennium, he said.

In the Yakima Basin, it’s a major step forward. This federal authorization comes a decade after a diverse group of water stakeholders in the region — including irrigators, the Yakama Nation, environmental groups and regulators — began to work together on a consensus plan to bolster water supplies for farmers and river flows, add fish passage to the region’s reservoirs and protect habitat.

Washington state lawmakers approved the 30-year, $4 billion vision in 2013 and have allocated $200 million so far for projects, including a major conservation land purchase.

Work on some aspects, including fish passage, habitat improvement and irrigation water conservation, began under existing authorization, but the water storage components most critical for growers had still needed federal approval.

The plan has been heralded as a model for its collaborative, consensus-driven approach to water issues after decades of conflict and for its innovative solutions to help the basin — which depends on snowpack as a reservoir — adjust and thrive in the face of climate change.

“We’ve been talking to folks throughout the United States about how we’ve been able to get the former adversaries together,” Eberhart said. “Rather than the old way of doing business, asking the federal government to pay for everything, our approach is to have federal, state and local responsibility funding the projects.”

In 2015, Urban Eberhart took Good Fruit Grower on a tour of one of the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan’s first projects, piping laterals to increase water conservation on the Kittitas Reclamation District. Having those pipes in place in 2015 allowed the district to pump water backward into Manastash Creek to keep water flowing for fish, the sort of farmer-fisheries cooperation that would have been unthinkable before the integrated plan brought the groups together with a shared vision of a more resilient water system. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

In 2015, a drought forced Yakima Basin growers with rationed water rights to manage with just 47 percent of normal water supplies and cost them $122 million, making the need for the water supply aspects of the plan clear. It also gave proponents a chance to test out some unexpected collaboration.

Thanks to a recently installed pipeline — one of the plan’s first conservation projects — the Kittitas Reclamation District was able to run water from its main canal back to a creek to keep the water flowing and protect critical salmon habitat, Eberhart said. It was so successful the district installed siphons to do the same thing in other at-risk creeks, rerouting farmers’ water, before it arrived at orchards and hayfields, to help fish survive.

“We didn’t know we were going to be so innovative, but we’ve continued to do it each year since,” he said. “That snowpack drought gave us a look at what it’s going to be like 25 years from now and we learned so much in a short time.”

When the next drought hits, growers on irrigation districts with rationed water rights hope to benefit from a $200 million investment in a floating pumping plant on one of the region’s existing reservoirs, which will tap into 200,000 additional acre-feet in the pool below the existing outlet.

Funded by the farmers who benefit directly, the project is pretty cost-effective compared to ongoing investments in water conservation through canal piping, said Scott Revell, manager of the Roza Irrigation District. The district provides water to 70,000 acres, primarily planted in permanent fruit crops, along the eastern side of the Yakima Basin.

Congress also allocated $75 million for repairs and improvements on the Wapato Irrigation Project, part of the Yakima Basin system on the Yakama Nation Reservation that’s been beleaguered by deferred maintenance for years.

The integrated plan also includes fish passage facilities, stream habitat improvements, expanded reservoir capacity for river flows for fish, irrigation water conservation, groundwater storage and water marketing.

New reservoir construction, the most controversial aspect of the plan, is slated for later stages of the plan and is not yet fully designed, vetted, authorized or funded. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Related:

—Integrated water plan moves forward

—Watershed moment for grower, water plan

Leave A Comment