There’s little mystery to irrigating. Getting the right amount of water to a tree at the right time may be complicated, but it’s certainly not a guessing game, said Tim Smith, longtime Washington State University Extension specialist from Wenatchee, Washington.

Tim Smith

“The rules of irrigation are physics. It’s math,” Smith told growers at the North Central Washington Apple Day conference in late January at the Wenatchee Convention Center.

Throughout his 30-plus years of grower outreach and education, Smith has recommended a set of intricate but standardized rubrics for growers to determine how much water their trees need, taking into account a host of factors, such as number of sprinklers, calendar date and soil type.

All of these points are knowable and can be plugged into an equation to give a grower a good irrigation recommendation.

“It’s complicated, but it’s important,” he said.

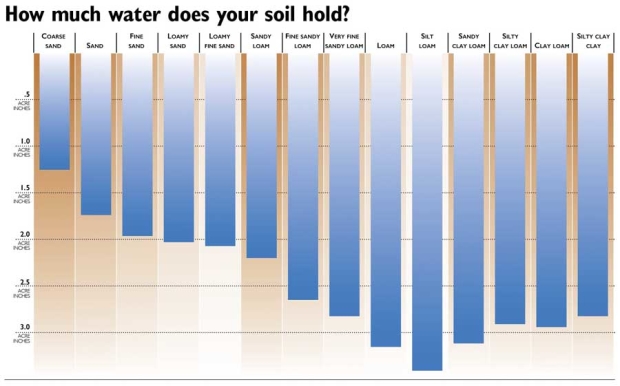

CLICK TO ENLARGE The amount of “usable water” held in an orchard’s root zone can vary significantly depending on the type of soil. This chart shows how some common soil types affect the usable water per acre inch in an orchard with a 3-foot deep root zone, which is typical for an older, vigorous rooted orchard. An acre-inch of water is about 27,150 gallons. Source: Washington State University (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

Smith, who is semi-retired, and Tianna DuPont, the extension specialist hired to replace him, have published a worksheet that walks growers through the process.

Overall, they encourage growers to use math, science and accurate data to deliver the correct amount of water, fully expecting that figure to change with the season and weather.

Smith bases his figures on evapotranspiration, the ever-changing rate at which trees consume water to process light and carbon dioxide to grow.

He suspects too many growers just guess in a high-stakes era of drought threats, shallow root zones and high-density plantings. “We have a problem when it comes to irrigating properly as an industry,” he said.

He doesn’t consider growers careless, he said, just stuck in a complex situation with a variety of planting structures, soil types, varieties, irrigation delivery systems and, in bad years, the shifting supply of water.

For instance, sandy loam and loamy sand have two different water holding capacities, which is the amount of water left in soil after it has been soaked and allowed to drain but not dry.

“I think most growers throw up their hands and surrender to the complexity of the situation and just try to keep from falling behind,” Smith told Good Fruit Grower.

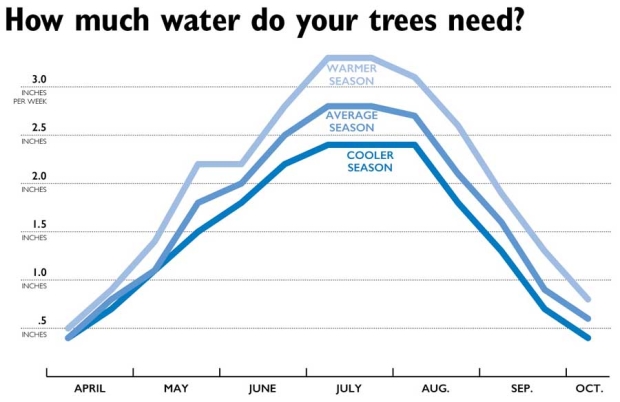

But taking the easy way out by using a set irrigation schedule for the entire season will give them the correct amount of water only twice, once in the spring and once in the fall. At all other times, the trees’ fluctuating needs rise and fall.

Meanwhile, Smith suspects many well-meaning but over-enthusiastic orchardists over irrigate in the spring when irrigation districts open the gates.

He suggests leaving trees alone in April and using the water instead to wash cars, fill spray tanks, control frost and top off on-farm reservoirs, postponing irrigation until May.

“Most people can’t resist putting that first set on,” he said.

But that may do more harm than good, he said. The first irrigation is usually the time of the first powdery mildew infection in cherries and may even spread fire blight in apples or pears in warm weather.

Also, overwatering in April can reduce root growth and flush out recently added iron and boron and reduce the trees’ uptake of phosphorus.

Too much water (as well as too little water and a host of other causes) can lead to iron chlorosis in fruit, a yellowing of the leaves caused by iron deficiency. Iron chlorosis is a relatively mild problem, he said, but avoidable for the trees in Washington.

CLICK TO ENLARGE – The amount of water that trees need is calculated based on the evapotranspiration rate, which varies depending on temperature, time of year and where the orchard is located. This table, using average numbers provided by WSU Extension Emeritus Tim Smith, charts water needs per tree for a standard older style apple orchard using overhead sprinklers. These numbers are applicable for Washington State University’s Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center in Wenatchee, Washington. Smith notes that these numbers would be higher in warmer areas of Washington and lower for cooler, higher-elevation orchards. Source: Washington State University (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

“They’d be a whole lot happier if they were drier in April,” he said. “There’s no pressure on them for water. They can be sitting in dry soil and be just as happy as clams.”

DuPont suggests growers use a common soil moisture monitor, and, as part of her research project, is volunteering to visit growers in their orchards; some have taken her up on the offer already. Growers also can send soil samples to their local soils lab.

Meanwhile, growers can access the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s soil survey, also online, to help them determine their soil conditions based on address or latitude and longitude coordinates.

The survey uses data from 1930s soil surveys, so it’s not perfect, DuPont said. “We’re just trying to get you close,” she said.

And WSU’s Ag Weather Net has an irrigation calculator that crunches the numbers for you, she said. For each field, the calculator will determine if plants are stressed based on soil type, the evapotranspiration for the crop and the irrigation rate. •

– by Ross Courtney

Help with your irrigation schedule

Tim Smith’s irrigation needs worksheet is available on the WSU Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center website at bit.ly/1ni9JkC. More irrigation decision aids can be found at WSU’s Ag Weather Net at weather.wsu.edu and at WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center at iarec.wsu.edu. Soil types can be found at the USDA’s Web Soil Survey site at 1.usa.gov/1QLNviu

Editor’s note: Additional information about where watering results were gathered was added to the second graphic “How much does your tree need”.

Leave A Comment