Growing peach, plum, and nectarine trees in sand tanks allows researchers to control all the nutrients used in tree development.

(Photo by Scott Johnson)

A study in which full-sized stone fruit trees are grown in sand tanks is yielding valuable data that will help scientists revise nutritional guidelines and threshold levels. Considered a definitive study on peach, plum, and nectarine nutrition by industry officials, the study allows researchers to determine for the first time the detrimental effects and benefits of specific nutrients on the health of stone fruit trees and fruit quality.

In 2000, Dr. Scott Johnson, University of California research scientist, installed 60 tanks measuring 6 feet by 12 feet and 4 feet deep, and filled each one with 19,000 pounds of sand. He planted Zee Lady peaches, Grand Pearl white-fleshed nectarines, and Fortune plum trees in each tank. White-fleshed peaches and nectarines make up about 20 to 25 percent of California peach and nectarine production.

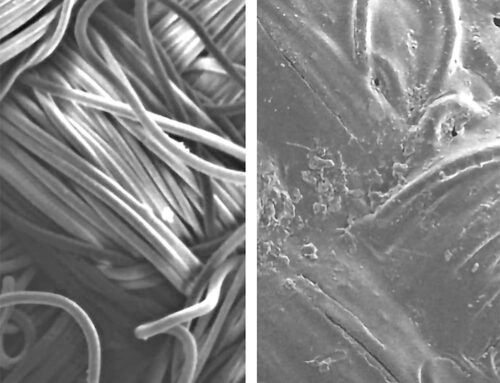

Nutritional studies on white-fleshed stone fruit haven’t been done before. The sand holds the tree up but supplies no nutrients, allowing researchers to spoon-feed all the nutrients for tree development. One by one, macro- and micronutrients were withheld from the mature trees, including nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, boron, and zinc. “We’ve been able to control the nutrients reasonably well,” Johnson said, adding that they are learning new things, particularly about phosphorus levels.

“We’re starting to see the effects of deficiencies in the tree before it shows up in the leaves as damage or symptoms,” he said. Kevin Day, UC Cooperative Extension tree fruit advisor, shared preliminary data from the sand tank project with Washington stone fruit growers during a soft fruit meeting held in Buena, Washington. Day said that the research team observed a distinct phosphorus deficiency in mature fruit trees. Only one other case in the South has documented phosphorus deficiency in soft fruit trees.

“We knew that you can have a phosphorus deficiency in young trees, but not in older trees.” The phosphorus-deficient trees were weaker with smaller leaves. Cracking and russetting was found on the fruit, especially in nectarines, which seem to be more susceptible to cracking. Johnson said that phosphorus deficiencies may have fooled growers and consultants in the past because deficiencies weren’t expected on mature trees.

“Most growers would probably throw nitrogen at the tree when they see such symptoms,” he said. “But in reality, it may be something else, like phosphorus.” After gathering sand tank data for several years, the research team is expanding the nutritional study to commercial orchards, surveying 60 orchard sites that are in sandy soil conditions.

They will use data collected from the field to determine average nutritional levels found in commercial orchards and fine- tune nutritional recommendations and guidelines. Nutritional levels for stone fruit trees were first developed about 50 years ago, according to Johnson. “Nutritional studies have been ongoing throughout the years, and the recommended levels for nutrients like nitrogen, boron, zinc, and phosphorus are constantly being tweaked.” Armed with this new data, Johnson plans to tweak the recommended nutritional levels once again when the field work is completed.

New sampling method

An outgrowth of the sand tank nutritional research is the development of a new sampling method using dormant shoots to determine the nutrient status of fruit trees. By collecting dormant shoot samples in January and analyzing the nutritional status, growers are armed with nutritional information going into the growing season.

They can make nutritional adjustments in the first half of the season. Growers typically collect leaf samples in midsummer to determine the nutritional status of stone fruit trees. Fertilizer applications are then made in midsummer or fall when it is often too late to help the current crop. Some nutrients applied in the front end of the growing season can benefit the current year’s fruit growth.

“With the dormant shoot technique, you can get an idea of what is stored in the tree and what it will take up in the spring,” Johnson added. The dormant shoot method can also be used as a tool to help growers gauge the effectiveness of previous fertilizer applications. He noted that the shoot sampling method might work better for some nutrients than others. The amount of nitrogen in dormant shoots was not that much different than the nitrogen amounts found in shoots from trees that the scientists knew were nitrogen deficient.

“It may be that for nitrogen, we have to measure it in a different way, such as measuring arginine or other amino acid levels,” he said. After samples from the commercial orchards in the study are analyzed, Johnson plans to publish revised nutritional threshold levels for several nutrients. Preliminary data already suggests that deficiency thresholds can be lowered for zinc, while the threshold levels for boron may be higher than what was previously published.

Leave A Comment