The Washington wine industry is targeting the tiny grape mealybug in a big way. Together, the industry leveraged a state research grant to develop areawide sustainable mating disruption and funded related research to evaluate perimeter use of mating disruption. Next, we are helping to launch research on a national scale.

For nearly two decades, the Washington wine industry has supported research at Washington State University to manage grapevine leafroll virus and its main vector, grape mealybug. We learned a host of things, including the importance of clean plant material, roguing infected vines to slow disease spread, the remarkable efficiency of the pest in spreading the virus, the economic impacts of the virus from yield loss and reduced fruit quality, and more. Despite efforts to curtail and control grape mealybug, we have not slowed the spread of leafroll virus.

At low infestation levels, grape mealybug feeding on grapevines isn’t a big deal in wine grapes. However, coupled with leafroll virus, the tiny insect becomes an effective vector for grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3, the predominant strain in Washington vineyards. Research has documented the rapid spread of leafroll virus in new or replanted vineyards just in their second leaf. Because it only takes a few mealybugs to spread the virus, even low populations must be controlled.

Leafroll virus — for which there is no cure — causes reduced yields, poor vine growth, uneven and delayed ripening, reduced fruit quality and shortened vineyard longevity. Leafroll virus ranks as a top research priority for Washington growers and wineries, according to industrywide surveys conducted annually by the Washington State Wine Commission.

Leafroll virus and its vectors are global issues. Fortunately, we do not have vine mealybug in Washington, which is more prolific than its cousin, grape mealybug. In California, vine mealybug has three to seven generations — depending on location — to control each season, compared to grape mealybug’s two.

Sustainable approach

Three years ago, grape mealybug research supported by the Washington wine industry began a more sustainable trajectory. Grape mealybug insecticides are expensive and can easily top $300 per acre, with no guarantee for complete control. There have been insecticide failures due to resistance.

That led to an interest in mating disruption, which is suitable for organic production as well. Preliminary data for a mating disruption program gathered by Doug Walsh, a Washington State University entomologist, showed promise for success. The Washington State Wine Commission leveraged his work into a $205,000 research project that was funded in October 2022 by a grant from the Washington State Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Block Grant Program. The 2024 growing season is the second year of this three-year grant.

The project’s goal is to develop a sustainable mating disruption program for grape mealybug in Washington vineyards. We believe mating disruption as an areawide strategy will provide the best chance for long-term, sustainable management of grape mealybug and, therefore, leafroll virus.

The use of synthetic sex pheromones to confuse males and prevent them from finding females to mate is successfully used to control many pests, including vine mealybug. Grape mealybugs are late to the sex pheromone party because the synthesized chemical is expensive and difficult to produce.

We are appreciative of the generosity of Trécé and Pacific Biocontrol, who have provided grape mealybug pheromone dispensers for our Specialty Crop Block Grant project (see “Producing and emitting befuddling pheromones”).

Preliminary findings

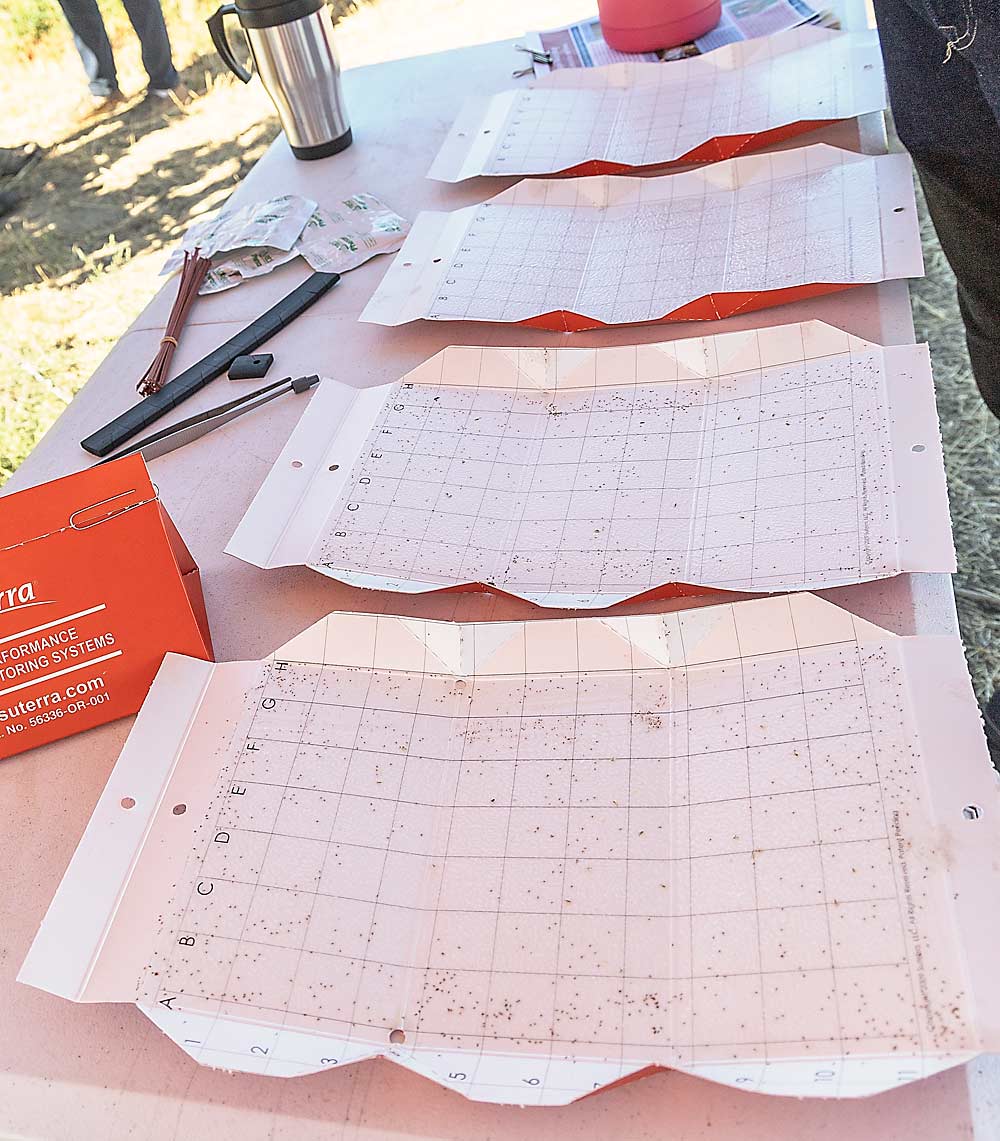

In the first grant year, Walsh received 2,000 twist-tie dispensers from Pacific Biocontrol Corp. and 1,500 puzzle-piece dispensers from Trécé Inc. Although larger trials were planned, only enough product was received to conduct trials in two replicates of 5 acres. Rates for Pacific Biocontrol dispensers were 0, 10, 30, 60 and 100 per acre, while the Trécé CideTrak dispensers were deployed at 0, 32 and 50 per acre in three 5-acre replicate plots per treatment. Two sentinel delta traps, baited with grape mealybug pheromone lures from Trécé, were used in each replicate to monitor flights of male mealybugs. One site was a conventional vineyard, the other a certified organic vineyard, both in Paterson.

Two mating flights were observed, with the first flight occurring in the latter half of May, followed by a protracted lull in capture from mid-June to late July, when the second flight occurred. In both mating flights, as few as 10 dispensers per acre substantially reduced trap capture in the sentinel traps. In the blocks with higher numbers of dispensers — 50, 60 and 100 — there was nearly complete shutdown in grape mealybug capture, which means that no males were captured. When males can’t follow the pheromone to the trap, it is assumed that they are overwhelmed with pheromone and unable to find females.

The Washington wine industry is also funding research to learn if pheromone dispensers deployed in a perimeter treatment can protect newly planted vineyards. The perimeter trial was conducted in two young vineyards near Benton City’s Red Mountain AVA. Dispensers were deployed in a 50-foot perimeter around two 5-acre vineyard blocks that were 2 and 3 years old, at rates of 50 per acre for Trécé and 60 per acre for Pacific Biocontrol dispensers. Sentinel traps were placed in the interior of the vineyard. Though complete shutdown of male captures did not occur in the sentinel traps, male captures were reduced enough that mating disruption would be likely.

Mealybug abundance in these young vineyards appeared to be low, based on visual observance, but up to 150 male mealybugs were trapped in one week. This demonstrates how quickly grape mealybugs can invade and colonize young vineyards planted in proximity to older vineyards.

Overall, early data indicates that when enough pheromone is deployed, mating disruption achieves complete trap shutdown. As we prepare for the second year of trials, we hope to receive increased supplies of pheromone.

A key component of the grant is to learn if controlling grape mealybug also slows the spread of leafroll virus. The grant supports sampling of vines and tracking the spread of virus by Naidu Rayapati, a WSU grape virologist. Data collected to monitor leafroll virus in the trials are still under analysis.

National focus

Leafroll virus was highlighted as a research priority during the Grape Industry Workshop held by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service in November in Beltsville, Maryland. The National Grape Research Alliance, of which the Washington State Wine Commission is a member, sponsored the workshop to share research priorities and emerging challenges with ARS scientists and leaders and to launch new research projects to address critical needs. Early detection of leafroll virus and its vectors was identified during the workshop as a high research priority.

In the coming months, the wine commission will work with the alliance to assemble a research team of stakeholders and scientists to flesh out a research proposal and seek grant funding. The alliance used a similar approach to secure the $4.75 million USDA-National Institute of Food and Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Research Initiative grant for the High-Resolution Vineyard Nutrient Management Project led by WSU’s Markus Keller.

We have put a bull’s-eye on grape mealybug and leafroll virus. We will work to enlist the best scientific minds to take an innovative and transformational approach to controlling the vector and the disease. Within the state, we will work with WSU to develop areawide management strategies that will provide long-term, sustainable control.

—by Melissa Hansen

Leave A Comment