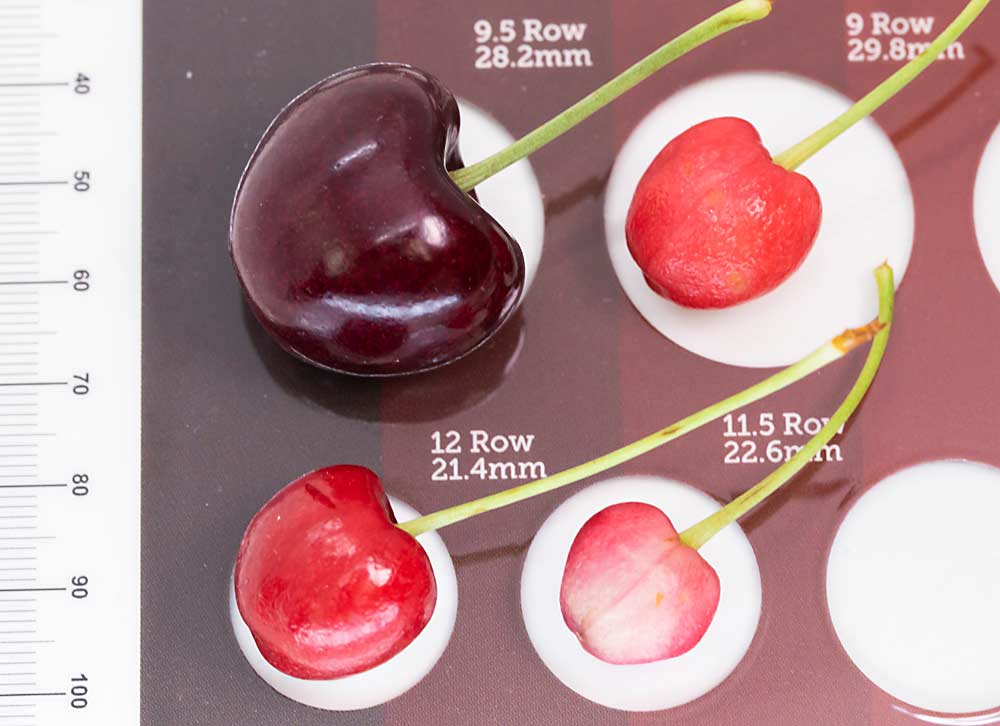

Only as harvest nears do cherry trees show signs of little cherry disease, bearing small, pale, bitter fruit.

But industry leaders now say the growing problem needs to be on the radar all year long, and they’ve launched a new task force aimed at slowing the spread of the pathogens responsible until long-term solutions, such as disease-tolerant cultivars, can be developed.

The pathogens, little cherry virus 2 and Western X phytoplasma, are not new to the Northwest, but they are on a sharp rise, according to testing data from the Clean Plant Center Northwest. The center’s director, Washington State University virologist Scott Harper, presented the data at the industry’s winter meetings to warn that without response, the disease could be heading toward exponential growth.

Harper came to WSU in 2017, after working in the Florida citrus industry, and he said his alarm about little cherry disease stems, at least in part, from his experience watching the impacts of citrus greening, an insect-vectored bacterial disease that he said behaves similarly to Western X.

“In Florida, response was too little too late, and I don’t want to see the same thing happen here,” he said.

The task force aims to coordinate a comprehensive response, guided by research, extension and industry members, said WSU extension specialist Karen Lewis. “Every single person I asked to participate said, ‘Yes, this is important,’” she said.

After the first meeting in April, the group decided to spend this year developing a plan of research, extension and policy priorities and then seek funding to get the most important work done first. Removing infected trees is only the first step.

“Just from a simple pathology perspective, we can’t just live with these two pathogens. That tree will keep getting worse,” Harper said. “The only solution is the same one that was proposed 70 years ago: Take it out.”

That sounds simple enough, but many questions remain, including: whether to remove asymptomatic, neighboring trees, too; how to treat the roots of removed trees to limit spread; how and what to replant; how best to control insect vectors; and what native or other crop species could be reservoirs for the pathogens.

WSU extension specialist Tianna DuPont said that in the short term, the team aims to improve education about the problem and what growers can do now.

“People are aware that it’s a problem, but there is still known little cherry virus that is not being removed,” she said. “So, something is missing. Is it how to deal with it? The economics? That’s part of the awareness we still need to help people work on.”

Detection

One of the first priorities the task force faces is figuring out how to survey across the region, assessing the scale and scope of the problem. A map of where little cherry virus 2 and Western X have already been found will provide a foundation for many research questions, but the task force wants to find a way to balance the need for that information with protecting individual growers’ privacy.

In Oregon, OSU pathology graduate student Lauri Lutes started a survey last year and plans to continue this year, as part of her ongoing project and the goals of the task force.

“We definitely saw it in The Dalles, and we had people reporting symptoms in Hood River and other areas we haven’t sampled yet,” she said. So far, all the symptomatic trees on the Oregon side of the Columbia Gorge have tested positive for Western X, she said.

All the growers she worked with removed the symptomatic trees, Lutes said, but both the virus and phytoplasma pose a particular challenge because they can spread undetected to adjacent trees, and it’s not common practice to remove neighbors pre-emptively.

The industry needs rapid, affordable, accurate testing tools that can detect the pathogens before trees show symptoms, said Hannah Walters, a research assistant at Stemilt Growers in Wenatchee, Washington, and a member of the task force. Newly infected trees don’t show symptoms right away but are likely spreading pathogens.

“That’s the long-term big idea, so that we can get ahead of it,” she said.

DuPont agreed, adding that eventual eradication will depend on accurate tests for new infections, when viral levels are low.

“Otherwise, we’ll just have these reservoirs of the disease out there,” DuPont said. “We don’t want to let our guard down and have it creep back.”

Vectors

The main insect vectors have been identified — mealybugs transmit little cherry virus 2 and leafhoppers transmit Western X — but many questions remain about the relationship between the vectors and the pathogens.

“A big question remaining is, ‘How do these vectors move, and how does that movement affect the spread of the pathogens?’” said WSU entomologist Tobin Northfield.

For relatively mobile insects, such as leafhoppers, there’s a risk that a treatment causing insect dispersal could actually increase the spread of the disease, he said.

Although people tend to talk about little cherry disease as one problem, when it comes to vector control, mealybugs and leafhoppers are very different insects and managing them will likely require two distinct strategies, Northfield added.

There’s pretty good information available about how to control mealybugs, Walters said, but when it comes to leafhoppers, growers are left trying to manage them without understanding how they move on the landscape or when they are most likely to transmit the disease.

There are alternate hosts for the hoppers in the native vegetation, and research is underway to see which native plants might host the pathogens in addition to the vectors.

“It’s such a complicated problem,” Northfield said. “Because you have to deal with plant physiology, the pathogens and the vectors, we need people who can focus on each aspect, but really, to get a good understanding of the problem, you really need the whole task force.”

Breeding

The ultimate solution to little cherry disease would be cultivars that are resistant or tolerant of the pathogens. Harper and WSU cherry breeder Per McCord recently began a trial looking for these key traits in a variety of commercial cultivars and breeding parents.

“If we find something in this batch, it’s commercial or close,” in terms of fruit quality and horticultural performance, McCord said. Otherwise, he’ll have to cast a wider net for tolerance traits in the genome of wild cherry cousins, delaying the commercial benefit.

With two pathogens at play, with presumably different modes of action, it’s also unlikely one cultivar will show tolerance to both, McCord said.

He also noted that tolerance and resistance are quite different. “Tolerance implies that the pathogen can infect, but the plant doesn’t care,” McCord said. “Tolerance will still get you good cherries.”

Resistance, on the other hand, implies that the plant has some mechanism to fend off a pathogen from multiplying, Harper said. Mahaleb, a cherry rootstock, has a mechanism of resistance to Western X, but its “hypersensitive” response means the infected tree kills itself, he said. That’s clearly not the kind of resistance the industry wants.

But tolerant trees, while producing good cherries, would still serve as a reservoir for the pathogens, with potential to spread, Harper said. “Tolerance is a double-edged sword, but it’s still probably a better solution.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Related:

—Sniffing out diseases

—Be on the lookout for little cherry – Video

—Little cherry disease creates a big problem

Leave A Comment