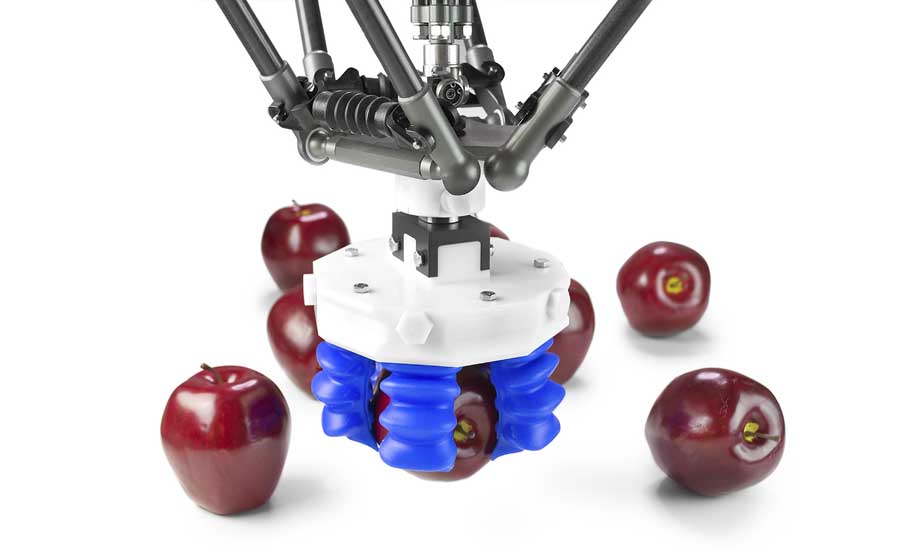

Soft Robotics demonstrates its air-actuated gripper in the robotics company’s Cambridge, Massachusetts, laboratory. The company planned a trial with Washington State University on ripe fruit in the orchards this fall. (Courtesy Soft Robotics)

One of the sticking points in the quest for automated fruit harvesters is how to handle fruit without damaging it. So far, nothing the robotic world has invented can compare to the finesse of the human hand.

The engineers at Soft Robotics, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, automation company, believe they are close, though. They make robotic grippers with fingers actuated by compressed air to gently curl around fruit and produce.

They planned to test how it works picking apples from a tree this fall during a trial at the Washington State University’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser.

“We’re confident that with the gripper that we’ve got the right tool for the job,” said Dan Harburg, director of business development for Soft Robotics.

For more than three years, Washington State University researchers have been working to develop a robotic hand that could harvest apples.

Manoj Karkee, associate professor of the university’s Center for Precision and Automated Agricultural Systems, said he and his colleagues have developed a three-fingered mechanical prototype that works, but probably not as fast as Soft Robotics’ air powered version.

“They have the advantage of speed,” Karkee said, but he said he is eager for more studies to see how fast the Soft Robotics version moves in the orchards.

The university’s robotic hand, mounted to a Gator, harvests about 85 percent of the apples at a rate between 5 and 6 seconds per apple. Karkee’s goal is 2 to 3 seconds per apple, he said.

Later this season, Soft Robotics planned to visit Karkee for trials of the rubber gripper in Washington orchards to see how fast their tool can go and exchange any other details about their respective robotic hands.

Robots can’t do everything

With either version, robotics are still a ways from putting pickers out of work, Harburg cautioned.

Robots don’t do everything pop culture makes them appear to do, at least not yet.

They work best in controlled environments in which the produce is brought to them on a conveyor belt, not when they must move around throughout an unstructured and varied environment, such as an orchard.

They don’t do two-handed tasks. They don’t collaborate with humans at speed.

And for all their sophistication, they still are limited in selecting and inspecting a good piece of fruit in the orchard, passing over a less savory one, the way an optical sorter can do inside the packing shed.

“That kind of complex product sorting … is challenging,” Harburg said.

The Soft Robotics hand is being used commercially in bakery warehouses and plastics plants and to handle consumer packaged goods.

They are still in trials at food packing facilities for mushrooms, tomatoes and strawberries.

“We are just at the beginning of evaluating the Soft Robotics gripper,” said Richard Harnden, director of research for Berry Gardens, one of the United Kingdom’s largest berry and stone fruit production and marketing companies. “Regrettably, it’s far too soon to make any informed comment.”

The mobility and vision for orchards and fields will come next for the robotics industry. In fact, the company has tested its hand on apples, Harburg said, placing them on a sample tray at the November 2015 Pack Expo in Las Vegas.

“I think all this stuff is coming quickly,” Harburg said.

Harburg showed the gripper at the Precision Farming Expo in January in Kennewick, Washington, sharing pictures and video of the rubbery digits deftly lifting and moving ripe tomatoes, mushrooms and cupcake papers. Others picked up sticks of celery and carrots in different orientations, arranging them in a uniform formation.

The problem is more than just delicate surfaces, Harburg said. Robots can be made gentle and precise. The automotive industry uses them for tasks both heavy and light.

Even in the food industry, robots frequently stack boxes or shrink wrap products. But all those tasks involve repetitive motions with objects of similar dimensions. Food in the fields — cherries, apples, eggs — are unique.

That’s one area the “octopus inspired” gripper could fit, adapting to a variety of shapes and sizes, he said. With rising costs of labor and increased food safety scrutiny, more robots may be on the way for farming.

“We’re going to see an explosion in what robotics can bring,” Harburg said.

– by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment