Where are workers and their families safer during a predawn pesticide application to the orchard adjacent their house: indoors, with windows and ventilation closed, or a nearby orchard block in the dark until the sprayer moves on?

That’s the dilemma Oregon’s Occupational Safety and Health division has been wrestling with the past two years, after the 2015 update to the federal Worker Protection Standards created a cushion area around active pesticide applications to prevent accidental exposure via drift.

That cushion, known as the Application Exclusion Zone, or AEZ, needs to be 100 feet when pesticides are applied to trees with an air-blast sprayer. It’s common in the tree fruit industry for worker housing to be within 100 feet of trees, but the original guidance from the EPA wasn’t clear about how housing fit into the AEZ rule.

So in 2016, Oregon proactively proposed allowing workers and their families to “shelter in place” inside during pesticide applications, as they typically have while sprayers work in nearby orchard blocks, and growers supported the proposal. But worker advocates said that this weakened the protective buffer from pesticide drift the AEZ rule intended to create, especially considering that some farm working housing is in poor condition.

Now, the state is poised to approve a new compromise rule that frustrates farmers and disappoints worker advocates at the same time the Trump administration is signaling plans to change and possibly eliminate the AEZ rule entirely. At press time, Oregon OSHA said a decision on the proposed rule was expected soon.

“Our frustration is that there is no real reason to do this,” said Mike Doke, director of the Columbia Gorge Fruit Growers, which represents 440 Oregon tree fruit growers. “If there was any indication that it was safer to evacuate, our growers would be the first ones to do that. Our growers live on these same orchard properties with their families.”

But, absent further clarification from the federal Environmental Protection Agency, evacuations appear to be what growers across the county will have to conduct this year to comply with the AEZ rule as it now stands.

A fact sheet on the rule released by the agency in February states that: “Agricultural employers must not allow any worker or other person (other than appropriately trained and equipped handlers involved in the application) in the AEZ that is within the boundaries of the agricultural establishment when the application is occurring. This includes people occupying migrant labor camps or other housing or buildings that are located on the agricultural establishment.”

The EPA declined to answer Good Fruit Grower’s questions about how those evacuations are expected to occur, what it would cost growers and what aspects of the AEZ rule it intends to change.

In Washington, state pesticide compliance program manager Joel Kangiser said that the federal requirement is clear that housing within the AEZ must be evacuated. “The only persons that can be within the AEZ are properly trained handlers,” he said. “It’s pretty black and white.”

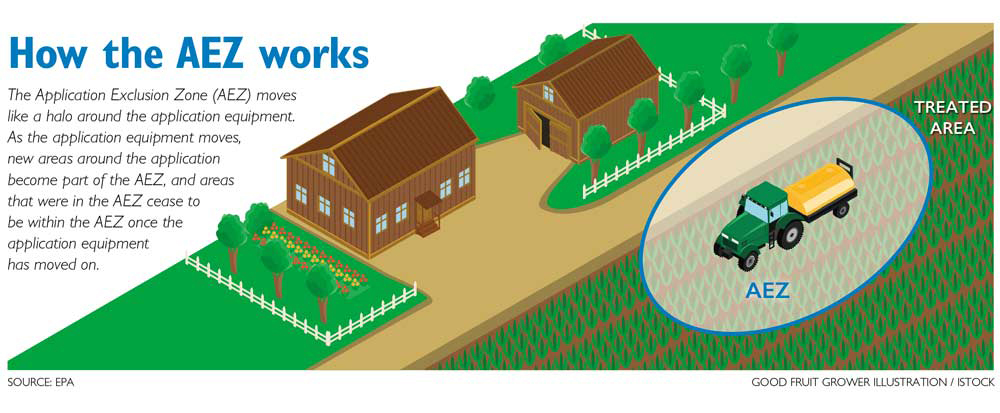

How the AEZ works: The Application Exclusion Zone (AEZ) moves like a halo around the application equipment. As the application equipment moves, new areas around the application become part of the AEZ, and areas that were in the AEZ cease to be within the AEZ once the application equipment has moved on.

(Source: EPA. Good Fruit Grower Illustration/iStock)

Oregon

In Hood River and Wasco counties, where tree fruit growers employ about two-thirds of the state’s farm workers and have about 200 registered labor camps and many more unregistered single-family homes for workers, concern about the impact of the AEZ rule is high.

Oregon OSHA administrator Michael Wood said the state’s proposed rule “would be both more protective of workers and more flexible for growers than the EPA rule.” People would still be able to shelter in place in housing within a 100-foot AEZ for airblast applications of pesticides that don’t require the applicator to wear a respirator, indicating that the chemical only poses a skin contact risk. For pesticides that pose a respiratory risk, the AEZ would expand to 150 feet and require evacuations.

Growing threats from pests such as spotted wing drosophila and brown marmorated stink bug may require the use of more harsh chemicals than growers normally use and invoke that 150-foot buffer, Doke said. So, some growers feel the rule will force them to rip out rows of trees to create a buffer around housing, taking a toll on productivity.

That cost is not considered in the state’s fiscal impact statement, because the only thing the rule would require is removal of people from the AEZ, Wood said in a statement. No costs are estimated for evacuations either, just for the time required to issue spray notifications and set up a notification station at each housing site.

Doke called it a “flippant attitude” for the public agency to assume growers would just opt to regularly evacuate workers and their families, often including young children, into an adjacent orchard block in the dark and cold, because there is no cost.

“We don’t want to create a climate of fear with the workforce where all of a sudden, because of no scientific data, people have to evacuate in the middle of the night,” he said. “They (OSHA) haven’t been concerned about what folks are going to do when they are evacuated.”

Parkdale pear grower Adam McCarthy said he’s frustrated by the lack of information from both the state and federal agencies about what the evacuation process is supposed to look like and what it will actually cost.

“Our predominant housing use is families, so we’re talking small kids. Do I want small children out in the cold and the dark for even 15 minutes? No,” he said. “If I can take out a row of trees and not have to evacuate them in the middle of the night, I’m going to do that. It’s far better to have happy employees that don’t have to get their families up in the middle of the night, even if agencies claim that doesn’t have a cost.”

But he said the loss of productivity to create those buffers will hit smaller growers like himself, who have lots of scattered single-family housing, much harder than growers elsewhere who have land space to build large worker complexes.

The Oregon-based Beyond Toxics, PCUN-Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (Northwest Treeplanters and Farmworkers United) and NOWIA Unete-Center for Farm Worker Advocacy also criticized Oregon’s proposal in a March letter stating that the shelter-in-place option fails to address the risk of drift and residue in labor housing.

“Farm workers and their families need a true no-spray barrier that creates a safe distance between living areas and pesticide sprays,” they wrote to OSHA. “Spray drift and take-home exposure can negatively impact family members, including children and others, even with low-level exposure over a period of time.”

Beyond Oregon

The issue of how housing located in an AEZ should be handled has been relatively quiet elsewhere, as farmers focused on figuring out how to comply with the rest of the updates to the Worker Protection Standards. Those include: additional training, notification and record keeping requirements; respirator fit tests for handlers; establishing decontamination and pesticide information stations; and preventing workers under the age of 18 from applying restricted-use pesticides or doing early entry work.

Most of the educational material on the federal AEZ rule has row crops in mind or scenarios when spray drift could pose a risk to workers present in an adjacent field. Unlike a buffer, the AEZ only exists while an application is occurring, and unlike the treated area, it is not subject to re-entry intervals.

But that could all change.

The EPA plans to propose changes to the AEZ rule, the agency announced in December, along with the WPS’s minimum age requirements. It offered no further details, but in March, a group of Democratic senators sent the EPA a letter expressing alarm at the agency’s move to “reconsider two federal safeguards that are vital to the protection of agricultural workers and children against dangerous pesticides.”

But many states, including Washington and California, have already updated their own regulations to be consistent with 2015 federal Worker Protection Standards, including the AEZ.

If the EPA does decide to rescind the AEZ rule, it would then be up to states such as Washington, where it’s now a part of state rules as well, to decide whether to retain, alter or drop the AEZ regulations, Kangiser said.

This uncertainly leaves growers across the country in a frustrating gray area. For now, complying with the federal rule means evacuating housing that would fall within an AEZ (unless state regulators have adopted more specific rules like Oregon proposes), but it may be premature to remove trees to create a buffer around housing if the rule will soon be changed. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment