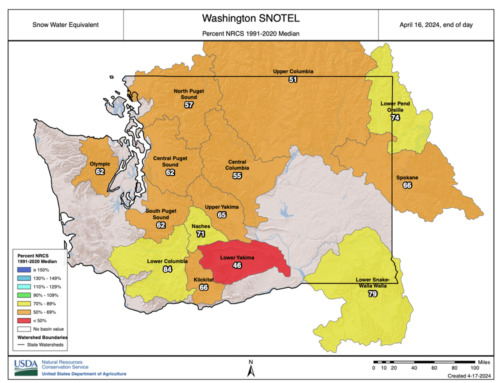

Figures ranging from 30 to 50 percent of normal snow and rainfall rates have been measured throughout the Columbia River watershed. Growers dependent upon surface water for irrigation are facing a potential loss in production.

Irrigation is the lifeblood of production in central Washington.

Grapes need in excess of twelve inches of water available to them during the growing season to produce a quality crop. The sandy soils that dominate the landscape in the Columbia Valley have a very low water-holding capacity, meaning most water must be supplied to the vines from sources other than dormant season rainfall.

With annual precipitation at less than ten inches in most areas, and most of that coming in the winter, irrigation must be applied in order to harvest a marketable commodity. Water for irrigation comes from either of two sources: surface water or ground water. Surface water comes from the year’s annual precipitation, captured in streams and lakes, then diverted into canals or pumped directly from the source.

In most years, surface water can be treated as a renewable resource, but some carryover capacity in large reservoirs is available. Unfortunately, some of the smaller systems, such as the Yakima River drainage, have such a small storage capacity that in any one year they can only store about 60 percent of their needs. This means that storage carryover from heavy rainfall years to drought conditions is minimal in some important production areas.

Surface water also has been in increasing demand by users other than irrigators. What little surface water is available this year must be split between three users: irrigators, power generators, and indigenous fish populations.

With a relatively sudden deficiency of power in the Pacific Northwest, water that normally might be diverted into irrigation canals may be used for electrical generation. Minimum stream flows must also be maintained in accordance with the Endangered Species Act. Irrigators may get lost in the wake of documents and litigation. Ground water offers limited potential for irrigation.

Water below ground level has a slow recharge rate, particularly during drought conditions. If too many people start pumping from wells, the static water level will drop. Shallow wells will go dry and may not recharge for years.

The Department of Ecology has been extremely stingy with well permits because it is concerned about a depletion of ground water, and rightly so. Existing groundwater supplies must be judiciously used, and new permits must be thoroughly scrutinized before approval. More wells are not the answer.

Grapevines don’t need much water to live. In fact, it is virtually impossible to kill an established grapevine by not watering it. There are a number of examples of abandoned grapes in eastern Washington that continue to live without irrigation. They don’t produce much fruit, but they continue to live.

Canopy management

Despite this rugged nature, growers need to make special plans in managing growth during drought conditions. The emphasis must be placed on canopy management. The first inclination may be to prune the vines short, minimizing the growing points and focusing growth into a smaller number of shoots.

Unfortunately, this strategy could easily backfire. Vigorous pruning coupled with a modicum of spring moisture, could result in what is known as the growth of “bull” canes, too large in diameter and with internodes longer than two inches.

This type of growth has been associated with poor winter hardiness and low production the next year. Prune normally to preclude an overvigorous situation. This should be followed by extensive shoot thinning after the weather warms up and vine water use skyrockets.

Shoots should only be left at well-spaced intervals (typically two shoots for each four inches of cordon length). Water applications should be modest when available to maintain the existing canopy but not to encourage more shoot extension.

Cluster thinning should be timed normally, after seed coat hardening and just before veraison. Thinning earlier may promote larger berries, something most winemakers don’t want to see.

Thinning to a single cluster per shoot may be needed, depending upon the severity of the water shortage, but, in any case, thin to leave the most well-filled cluster on the shoots to mature. In severe drought conditions, the crop may not even properly ripen. Leaves will yellow and cease photosynthesis prior to grape ripening. The vine will simply shrivel the berries, drop the leaves, and go dormant.

The big problem for the health of the vine will be going into the winter with dry roots. Vine dehydration during winter months can cause major amounts of vine damage and pose a serious threat should the drought continue into next winter.

Hopefully, the drought will not be serious, but problems farming grapes in such an arid climate as the Columbia Valley, particularly with the lack of enough storage reservoirs, will always be with us. It behooves grape growers to know how to handle their vines to reduce crop loss both this year and in succeeding vintages.

Leave A Comment