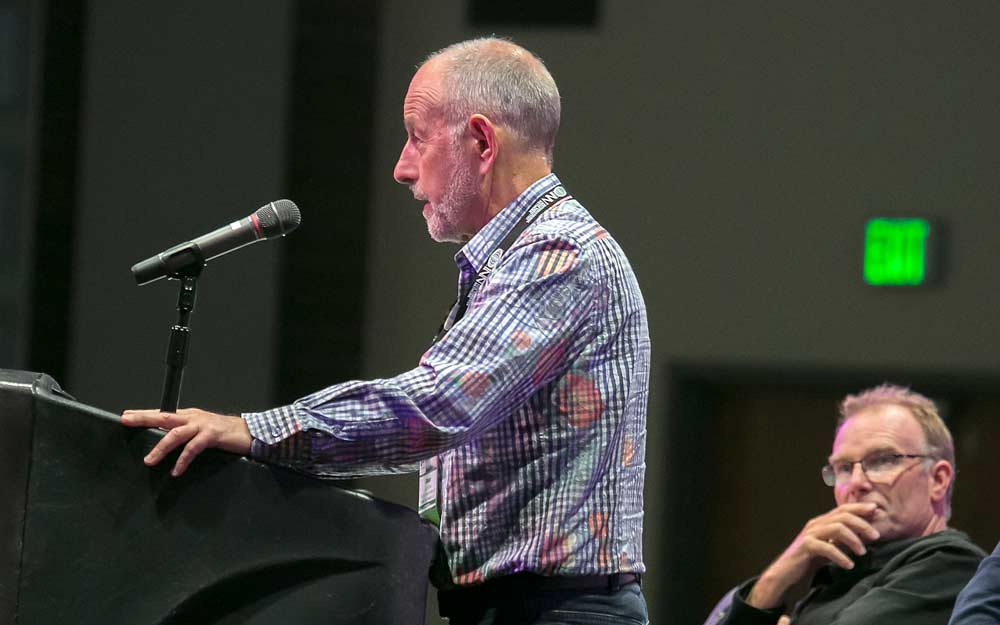

Divis shows IFTA attendees the result from his mechanized hedging trials on this two-leader planting in Brewster. He emphasized how close the hedger was able to prune the fruiting wall, allowing for more light to pass through the row. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Higher yields, better varieties and increasing efficiencies are accelerating deployment of new technologies in apple orchards, from biological mapping of varieties to novel spraying, hedging and harvest equipment.

The IFTA’s 60th annual conference in Wenatchee, Washington, in February, with a theme of “From Bud to Bin,” included speakers and grower tours highlighting new methods of establishing an orchard, growing a tree, growing fruit and ensuring harvest maturity.

New and emerging orchard systems proved to be a central theme.

What’s new in Washington?

During the industry downturn from 1998 to 2006, 50 percent of Washington growers left the apple industry.

Marketing companies consolidated. At the same time, the number of commercial varieties grown in the state ballooned from just three in the early 1980s to more than 30 today.

The number of rootstocks also increased dramatically, from three to more than 20 today.

Apples have really been a pioneering crop with the development of commercial rootstocks, a movement that enabled high-density plantings, said Stuart Tustin, a plant physiologist and science group leader at the Institute of Plant and Food Research in New Zealand.

Now, if growers and researchers can learn more about the natural growth and the horticultural traits of each cultivar, alongside those of the chosen rootstock, “we can make some big gains,” Tustin told Good Fruit Grower.

Craig Hornblow, right, listens to Stuart Tustin during an IFTA panel discussing orchard training systems and the importance of why better management of light can revolutionize future orchard productivity. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

“Farming often is a subjective activity, because you learned from your father, who learned from his father. Now, it’s on a scientific basis,” he said. “We’re shifting from being farmers to being engineers. My vision is that everything we do is vision based and numerically based.”

Much like a factory, where nothing is unexpected because every factor is objectively and measurably monitored.

Light interception

Jim Divis grows 200 acres of apples in Brewster, Washington, high up in an area called Brewster Flats overlooking the Columbia River. Varieties include Honeycrisp, Fuji, Pazzaz, Pacific Rose and Envy, planted as either two-leaders or a steep single leader.

Divis has begun experimenting with automated hedging immediately after harvest, both on several rows in a seventh-leaf Fuji block on Pajam 2 and on several rows in a newer Honeycrisp block on Malling 106.

The trees are planted in 5 foot by 10 foot spacing, with about 900 trees per acre.

In the first year, he found he was cutting off wood that was there for fruiting.

“We started quite away from the tree, then got it dialed in a little better and got closer,” he told attendees during a tour of his orchard. Once dialed in, the cuts were 6 to 8 inches in to try to push breaks above the cut. To balance the vigor in each leader, he headed the one that was lagging behind to help it catch up. “If some branches overcropped, then we would thin them down a little more.”

Divis said he won’t dormant prune again until next fall and that, with two leaders, it doesn’t really matter if it looks perfect.

“I’m excited about the potential going forward of having a tighter, smaller canopy with more light penetration,” Divis said. “Automated pruning — that’s pretty exciting.”

Light interception is a central area of Tustin’s research in New Zealand. His latest research block features a two-dimensional planar canopy where leaf area distribution enables higher irradiance of light throughout the orchard canopy.

Trees are spaced much more closely together, with about 3 meters between trees (nearly 10 feet) and 1.5 to 2 meters between rows (roughly 4 to 7 feet), and a canopy of 11 to 13 feet.

The number of trees planted per hectare is between 1,667 and 2,222, and the number of vertical stems per hectare is 10 times that number. One hectare is 2.47 acres.

It’s a system Tustin acknowledges breaks all the rules.

Orchards currently only use about a third to half of the available light over the course of a season, and productivity could be increased significantly if growers harness that light, he said.

“If we want more light interception, we have to bring the rows closer together. To do that, we have to change the design of the tree so that we satisfy all of the physiological requirements of the tree for fruit quality,” he said. “Our light modules are all developed on slender spindle type tree canopies. Our assumption of the moment is that they don’t apply to these very thin, two-dimensional canopies. Light modeling over time will provide a good indication of how fruit colors over time.”

Productivity

The biggest cost to growers, when you consider the question of orchard architecture from a financial perspective, is the time out of production — not labor, packing or freight, said Craig Hornblow, a horticultural consultant specializing in apples for AgFirst in New Zealand.

Other countries, such as Italy, are seeing their average yields going up because they are getting their orchards into production more quickly by employing simpler orchard systems.

And lost production time is the biggest cost that growers have to drive out of their business, he said. Orchardists today are growing four-, three- and two-dimensional canopies, yet, “we still have to just keep getting simpler. I’m convinced of that.”

Still, it’s not just about yield. Growers must also produce high-quality fruit, delivered at a size and in a variety that marketers can sell.

That means the orchard system needs to not only be simple — narrow, 3- to 5-foot rows with 50 percent shade — and accessible, attractive to work in and platform friendly, but also productive at 90 to 100 bins per hectare of targeted fruit, he said.

“It’s about execution. It’s excellent execution, attention to detail. It’s really difficult to do. You have to break it down into small units, but it’s doing the right job at the right time consistently,” he said.

And, he added, the new range of orchard systems, whether it’s two-dimensional or a V-trellis, gets growers much closer to that reality. •

– by Shannon Dininny

Leave A Comment