Choosing a V-trellis or a vertical trellis depends on how quickly you need to make money. Selecting varieties depends on the desires of the sales desks. Choosing rootstocks depends on … well, pretty much everything.

Myriad decisions await growers, each fraught with risk. But a panel of four Washington orchardists at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s annual meeting in December in Yakima, Washington, attempted to lower a few of those risks with some horticultural light.

“Risk comes from not knowing what you are doing,” said panel moderator Jason Matson, quoting Warren Buffet. “And so, we need to know what we are doing and, better yet, why we are doing individual tasks.”

Matson, head of orchard operations for Matson Fruit Co. in Selah, Washington; Scott Crawford, manager of Borton Fruit’s Flat Top Ranch near Burbank, Washington; Tye Fleming, an orchardist and nursery owner from Orondo, Washington; and Dan Plath of Washington Fruit and Produce Co. in Yakima riffed on everything from trellis design and fumigants to weed control and rootstock selection, all under the theme of reducing risk through horticultural practices.

Risk and cost go hand in hand, but they’re not always exactly the same thing, Plath said. After an orchard tour several years ago, Plath recalled grower Charlie de la Chapelle Jr. pointing out how an expensive-looking orchard management system may lower risk by reducing the things the grower can’t control. Many times, lowering uncertainty lowers risk.

Plath did not attend the panel due to illness but allowed Matson to present his slides and thoughts, and he participated with Good Fruit Grower on follow-up questions.

V versus vertical

The decision between planting on a V-trellis as opposed to a vertical trellis depends on how long you can wait for production.

Fleming, a small grower, considers vertical trellises a lower risk because his trees reach top production sooner, even if a V-trellis would get him higher yields in the long run. Lowering risk to him means maximizing returns in his first 10 years.

“To limit my risk, I want to plant cheap, I want to fill my space fast, I want to start getting tonnage in, and I may be giving up some long-term net present value for some short-term gain,” he said.

He favors a 2-foot by 10-foot, single-row vertical fruiting wall system, using super spindle techniques with no large branches. The system tops 10 feet and produces some crop in the second year, yielding 80 bins per acre at full maturity.

With new rootstocks to compete with Malling 9, growers can and should grow trees quickly while cropping moderately early, ramping up the yields as the trees age.

“To limit risk, we have to be able to grow and fruit at the same time, not one or the other,” he said.

His system also lends itself to mechanization; he plans to incorporate hedging this year.

Borton Fruit, on the other hand, favors V-trellises because they produce bigger yields in the long run, even though the company pays more on the front end, Crawford said. The company mostly plants 12-foot rows with 3 feet between trees. He shoots for an average near 100 bins per acre.

The higher yields of a V-trellis also please his labor pool, in short supply everywhere. The company has not yet tried to mechanize harvest.

The company does grow some Granny Smiths and Fujis on a 10-foot vertical wall.

“We’re kind of hedging and planting some of these systems that we think will lend themselves to mechanization, but we’re going to stick to what we know and what we’re doing well, so we are still planting some V-trellis,” Crawford said.

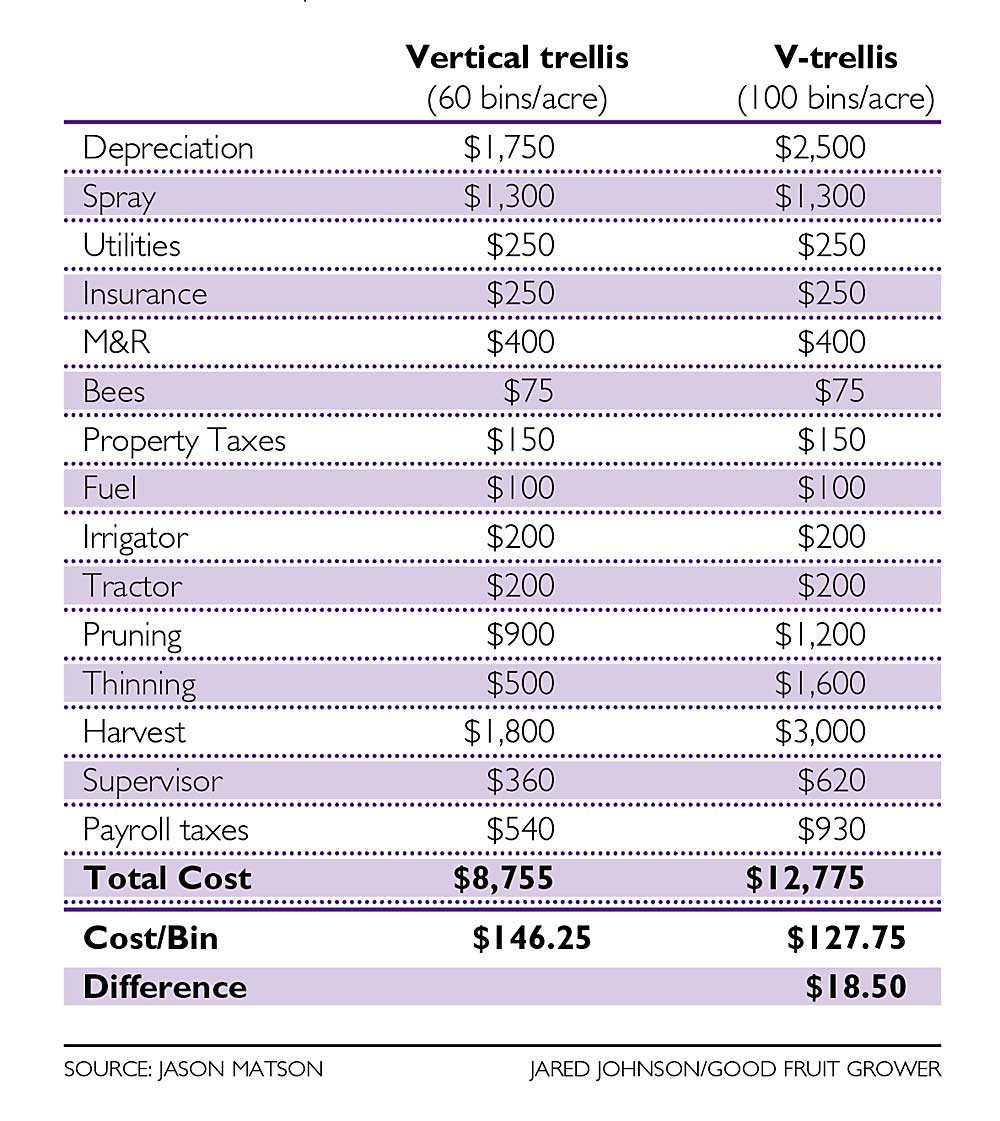

Yields make a big difference in measuring costs, and therefore risk, Matson said — and he attempted to quantify that difference in his presentation. For example, he figured it cost more per acre to grow apples at 100 bins per acre versus 60 bins per acre. However, the cost of growing each bin cost more at the lower yield (see chart).

Historically, Matson’s orchards on vertical fruiting walls produce around 60 bins per acre and between 90 and 110 bins per acre on V-trellis, scion varieties being equal, Matson said.

“Because of this, due to the high cost of capitalization of both systems, we feel V is less risky, because we feel our odds are better that the marginal benefit difference of V outweighs the marginal cost difference,” he said in a follow-up interview with Good Fruit Grower.

Generally speaking, mechanization is possible on both V-trellises and vertical trellises, Matson said. It’s just a little easier on vertical.

Plath agrees. Both systems work with mechanization, but he has found that equipment seems to be designed for wider drive rows than for many of his V-trellised blocks, which, planted at 10-foot spacing, are narrower than most of the industry.

“Manufacturers do their research on orchard systems to determine what size to build their machines,” Plath said in follow-up comments. “Sometimes the machines being built are too large for the 10-foot V.”

Varieties

The most important — but not only — factor in determining which varieties to plant is whatever the sales desks want.

“If they don’t want it, you shouldn’t put it in the ground,” Fleming said.

Crawford echoed that advice. He grows most varieties, including a few clubs, but bases his planting decisions on what the warehouses want. Borton sells through Chelan Fresh in Chelan, Washington.

The panelists also advised peering into the future by asking what might be coming next from nurseries. Also, factor in labor management, packing line timing and site selection when choosing new varieties, Matson said.

Rootstocks

The speakers gave the usual answer to questions about which rootstocks to use: It depends.

Crawford uses only Geneva rootstocks for any new plantings because fire blight pressure at his area near the Snake River is so high. Many Geneva roots are fire blight resistant.

Meanwhile, growers have to use what’s available, Matson said. He has been interested in G.214 for some time but has been unable to find enough of them, he said during a video interview with Good Fruit Grower after the panel. Then, he narrows the selection based on desired attributes.

Fleming, a grower and a nursery owner, uses the Geneva series but has no favorites. He just tries to match rootstock to situation. If he’s planting Honeycrisp on a bad replant site, he’s thinking G.890, but for Gala he prefers G.41. Meanwhile, he thinks G.11 struggles in sand.

He suggests growers scope out their neighbors to find out what works where, take soil samples from their own orchards, make their best educated guess and try several rootstocks.

The industry is early in the age of the Geneva roots and everybody is still learning about them. But don’t wait to have all the answers, he said.

Fleming advised growers to consider intermixing rootstocks within a block due to variances in soil, but be cautious. “It takes a lot of homework,” he said. “You really got to map your soils right.”

Here are a few other tips from the panel discussion:

—Matson has had good luck with metam sodium soil fumigant treatments for individual tree replants, especially in areas with fire blight. When replanting, his crew digs a hole in the fall, treats it with metam sodium and lets it work through the winter. In the spring, they reopen the hole and replant.

—For organic weed control, Fleming uses Suppress (caprylic acid and capric acid), an herbicide registered by the Environmental Protection Agency in 2015. “It’s a godsend,” he said. But he uses it sparingly, after burning and cultivation methods, just because it’s so expensive at nearly $60 per gallon. He also suggested buffering it to a low pH first.

—Crawford chooses rootstocks, such as those in the Geneva series, that mitigate fire blight risk and believes higher tree densities can also mitigate risk by diluting the cost of losing one tree. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment