Botrytis bunch rot and sour rot are not the same, and these clusters of white grapes demonstrate the difference between the two. The cluster at left is infected with bunch rot, and shows the telltale growth of Botrytis fungal spores (the gray, velvety fuzz). The cluster at right, on the other hand, shows the pinkish hue characteristic of white grapes infected with sour rot. (Courtesy Wendy McFadden-Smith/ OMAFRA)

Sour rot can be a frustrating foe in vineyards, but after more than a decade studying it, researcher Wendy McFadden-Smith has a good idea about what causes it, what makes grapes vulnerable and what can help keep it at bay in the vineyard.

“I first noticed it in some research plots during a spray trial for powdery mildew in a Riesling block in 2005 or so. I saw these berries disintegrating. I’d grab the cluster to rate and it would just turn to mush in my hand,” recalled McFadden-Smith, who is a tender fruit and grape integrated pest management specialist at the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). Put simply, she describes sour rot as “that vinegar and nail-polish smell.”

“The berries turn pinky-brown in white varieties and a brick red in red varieties, and generally they’re hollowed out,” she said.

Sour rot in Riesling causes not only “a vinegar and nail-polish smell,” but also increased volatile acidity (VA). High VA, in turn, can cause growers to lose entire crops. (Courtesy Wendy McFadden-Smith, OMAFRA)

Sour rot also causes a spike in volatile acidity (VA), which can lead to off-tasting wine, so vineyard workers spend many hours dropping rotted fruit and applying fungicides to try to stem the tide of rot. Despite their efforts, growers may still lose their entire crop because of high VA.

McFadden-Smith cautions that sour rot has been lumped together with Botrytis bunch rot historically, but they are not the same thing. “In the past 12, 15 years, we’ve learned more and differentiated them as very different complexes. I can find bunch rot without sour rot, and sour rot without bunch rot,” she said. That’s an important distinction, because bunch rot arises from infection with Botrytis fungus, but sour rot does not, so they require different treatments.

“There are fungicides labeled for use on both bunch rot and sour rot; however, if you examine the label carefully, you will note that only fungal pathogens are listed.”

What’s behind sour rot?

The underlying causal agents of sour rot are bacteria and yeast that get into the fruit through some kind of opening in the skin, often up where the berry is pulled away from its pedicel during berry-swell preharvest. The offenders include a variety of acetic-acid bacteria, including species of Acetobacter and Gluconobacter, as well as Hanseniaspora uvarum yeast. Once in the berry, the bacteria and yeast begin digesting the flesh.

By visiting this infected cluster, this vinegar fly could be picking up sour rot to later spread to other clusters. As part of an integrated approach, McFadden-Smith recommends insecticides to reduce these pests. (Courtesy Wendy McFadden-Smith, OMAFRA)

Fruit flies compound the problem, she said. “The run-of-the-mill vinegar flies (Drosophila melanogaster) can carry the yeast and bacteria on their feet and also in their gut, so they can vector it around. The other thing with vinegar flies is that they tend to lay their eggs around where the berry attaches onto the pedicel, so when the larvae come out, they can also enter the berry as it pulls away from the rachis as it swells and also feed on the flesh of the berry.”

Spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) may be vectors for sour rot too, she said, but so far, her research group is seeing much higher numbers of vinegar flies in the Ontario vineyards where the group conducts its studies.

Early-maturing, thin-skinned, tight-clustered varieties are most susceptible. In Ontario, the hybrid red Baco Noir comes down with sour rot first, followed by Pinot Noir, Riesling, Gamay and Gewürztraminer. Later-maturing varieties typically don’t succumb, she believes, because the weather at that point is just too cool for vinegar flies to be out and moving the disease through the vineyard.

“We’re also finding that any kind of injury when we get post-veraison and after the berries reach about 15 degrees Brix can get sour rot going, so that means splitting from rain, but injury can also come from things like wounding from birds, grape berry moth, or wasps,” McFadden-Smith said. And some grapes develop sour rot even without obvious wounding.

What’s the answer?

Over the years, McFadden-Smith and her research group have tried just about everything to fight sour rot. That includes using manual, mechanical and chemical leaf removal to loosen clusters, employing calcium and other supplements to increase skin toughness and reduce injury to grapes, killing the sour rot pathogens with antimicrobials and other chemicals and managing Drosophila populations.

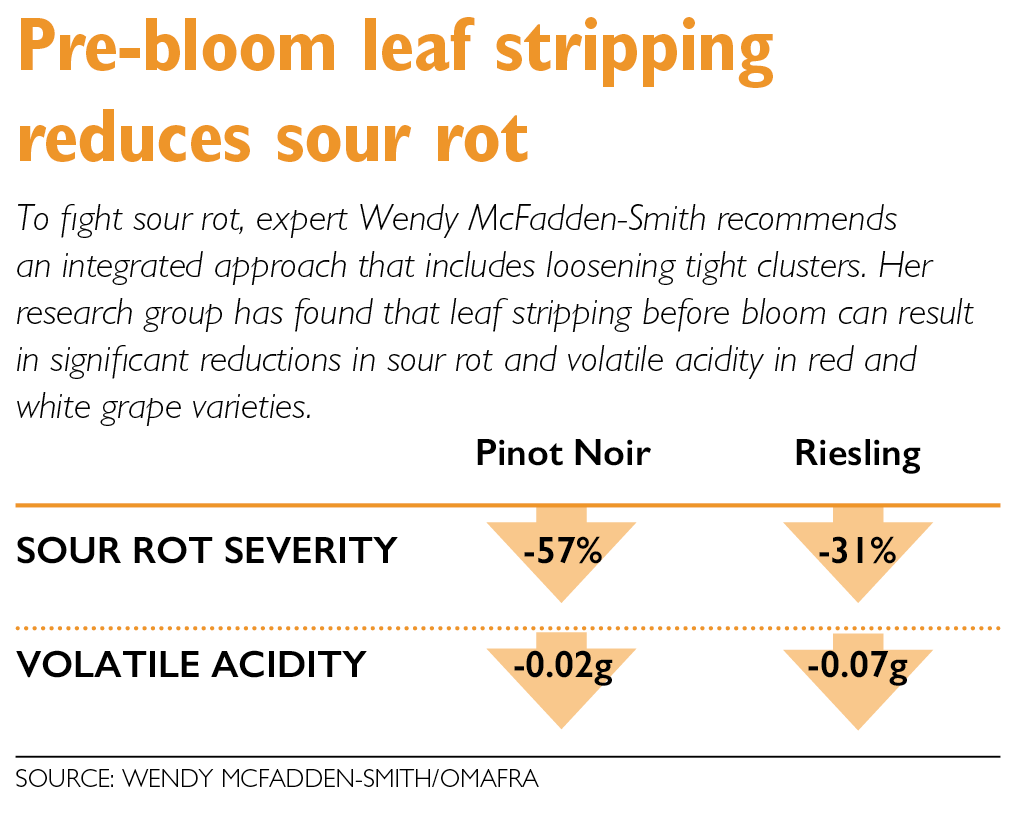

Of all the methods tried, leaf removal was the best and most consistent in ultimately reducing sour rot. Manual stripping of six basal leaves on each fruitful shoot, for instance, cut sour rot by 31 percent in Riesling and by 57 percent in Pinot Noir. “But really, as long as you get the leaf removal done before pea-sized berry, you’re probably doing OK,” she said. Experiments with gibberellic acid and prohexadione calcium (Apogee) also markedly reduced sour rot. On a side note, while some growers have expressed concerns that such leaf-stripping activity or growth regulator applications might have a negative impact on return fruitfulness, she said her group’s experiments have shown no significant effect on the number of fruitful shoots in subsequent years.

To fight sour rot, expert Wendy McFadden-Smith recommends an integrated approach that includes loosening tight clusters. Her research group has found that leaf stripping before bloom can result in significant reductions in sour rot and volatile acidity in red and white grape varieties. (Source: Wendy McFadden-Smith/OMAFRA)

Along with leaf removal, she also recommends the following sour rot-fighting strategies:

—To reduce fruit cracking and keep bacteria and yeast from entering grapes, use calcium or the silicic acid at two-week intervals beginning when berries reach pea size.

—To manage fruit flies and reduce the spread of sour rot, use an insecticide when grapes reach about 12 degrees Brix.

—To fight sour rot pathogens directly, apply an antimicrobial treatment at weekly intervals beginning at 12 to 13 degrees Brix. If the preharvest period is very rainy, the interval should be shortened. BlightBan A506 was the most effective antimicrobial product; Fracture, OxidateSerenade, Botector and Double Nickel were not as effective. In addition, food-grade potassium metabisulphite was also effective. (Check to make sure these products are approved for use in your area.)

“I’ve been working on sour rot since 2005, and I still don’t have all the answers, but the best bet is to use an integrated approach to fight sour rot in your grapes,” she said. “None of the treatments is a stand-alone solution.”

The research was funded by Ontario Grape and Wine Research. •

—by Leslie Mertz

Leave A Comment