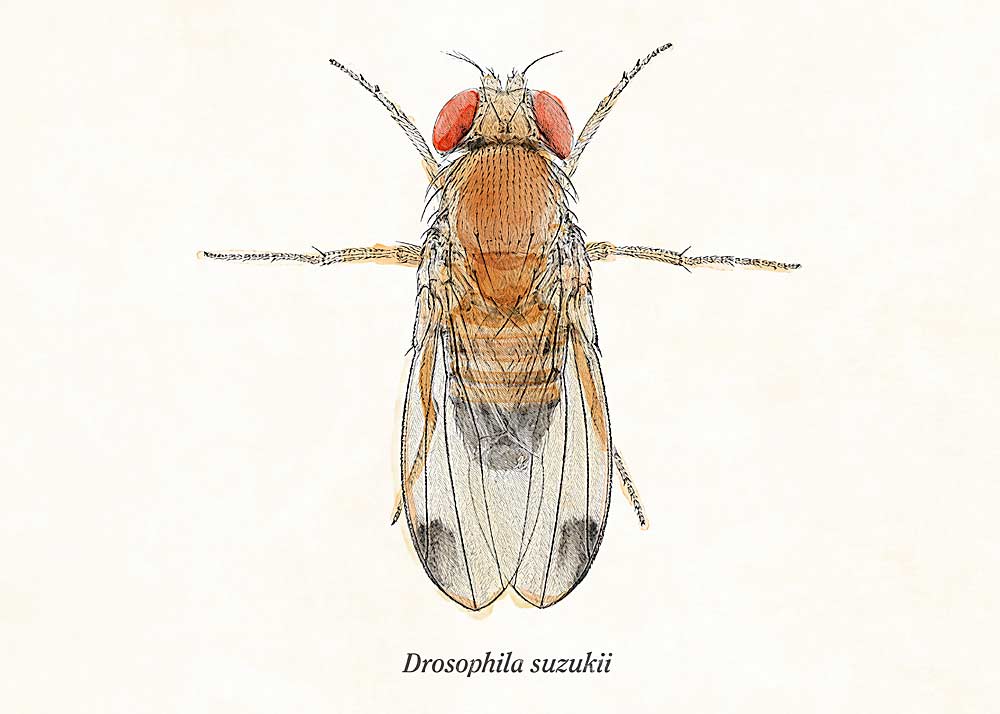

(Photo illustration: TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

New research from California demonstrates that spotted wing drosophila in commercial berry fields are developing resistance to the only organic insecticide effective against them.

Researchers have long thought that because SWD has so many hosts outside of commercial crops, access to those refuge areas would reduce the risk of the pest developing insecticide resistance. But it turns out that at least in an agriculturally dominated landscape with little untreated habitat, resistance is emerging.

“It’s the first warning that moderate levels of resistance are emerging,” said Brian Gress, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Davis, of his recent study. He began monitoring resistance in the Watsonville area in 2017, after reports from raspberry and blackberry growers indicated Entrust (organic spinosad) was losing efficacy against SWD.

He measured resistance by comparing flies from the Watsonville area with flies from an untreated orchard area a few counties away. Gress found that the Watsonville flies could withstand five to eight times more spinosad.

Exposing the flies to more spinosad in the lab for five more generations pushed resistance significantly higher, he added, suggesting that continued heavy use of the insecticide in the field will continue the selection pressure for resistance.

“This is primarily a concern for organic growers, because they don’t, at this time, have any other options to turn to,” Gress said.

However, conventional growers regularly use spinosad in their SWD programs, as well.

It’s a significant finding that highlights the importance of product rotation for resistance management, said Michigan State University entomologist Rufus Isaacs. But it’s also a localized finding that may say more about the intense selection pressure in the area, dominated by organic berry production, which may not be present elsewhere in the country, he added.

Entomologists across the country continue to monitor SWD for insecticide susceptibility, and this highlights the ongoing importance of that work, Isaacs said. To that end, he worked with colleagues in Michigan and Georgia to develop a new rapid screening test method for SWD resistance to malathion, methomyl, spinetoram, spinosad and zeta-cypermethrin, which Gress used in his study.

In Watsonville, Gress plans to study the spatial variability of the resistance to see if SWD on organic farms have more resistance or if SWD on the margins of the commercial farming region have less.

“So far, we haven’t seen a consistent pattern that this is worse on organic sites. The flies move around a lot,” he said.

He also plans to look at resistance to the related insecticide spinetoram (Delegate) and work with geneticists to understand the mechanism for resistance. In the big picture, he said it demonstrates the importance of ongoing work to find more management tools for SWD — both chemical and cultural.

“I think it would be a mistake to assume this is a problem restricted to Watsonville and we don’t have to worry about it elsewhere,” Gress said. “We’re recognizing that there is a real need for alternative organic management strategies.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment