In Spain’s central plateau, the wine region known as La Meseta, Tempranillo is king in a dry climate defined by warm days and cool nights.

“It’s a high-altitude table in the middle of Spain that looks a lot like Eastern Washington,” said Javier Alfonso, a native of Spain and owner of Pomum Cellars and Idilico, a Spanish-wine-focused winery, both in Woodinville, Washington.

Those climate similarities led him to believe the variety would be well-suited to the Yakima Valley — and it is, as people had a chance to appreciate earlier this year during a tasting session and panel discussion at WineVit, the Washington wine industry’s annual convention.

Brian Carter, of Brian Carter Cellars, said Tempranillo doesn’t reflect terroir the way some varieties do, and Spanish winemakers typically blend it — a practice his winery embraces. “Americans got on a varietal kick in the ’90s, but blends were traditional in Europe,” he said during the February panel. His Spanish-style red is primarily Tempranillo, blended with Graciano for the color and fruit character.

But while Tempranillo remains a dominant force in the global wine world, it’s a niche in Washington. That’s what makes it interesting, said grower Todd Newhouse.

“It’s a variety that you really can’t deficit-irrigate like you can other varieties,” he said at the conference panel. “In a nutshell, I’ve really learned a lot.”

Tempranillo 101

For a class on Tempranillo, WineVit turned to Geraldine Diverres, a native of Spain and a doctoral candidate at Washington State University, and Gavin Joll, the general manager of Abacela, a Southern Oregon winery founded on the pursuit of perfect Tempranillo.

“The name comes from the Spanish word ‘temprano,’ which means early,” Diverres said. One of the first varieties to reach veraison, the variety features low acidity thanks to an earlier ripening window during warmer conditions.

It’s a vigorous variety, known for large bunches and large berries, although mild water stress is beneficial to reduce the berry size. But the large canopies demand a lot of water, making Tempranillo very sensitive to deficit irrigation, she said.

Growers traditionally train the variety in a goblet system or a very-high-density VSP, Diverres said.

At Abacela, in Roseburg, Oregon, they grow about 25 acres of Tempranillo in a VSP system, after years of trial and error with spacings, systems and clonal selections, Joll said. The winery’s founders, Earl and Hilda Jones, moved to Southern Oregon in the early 1990s because they had determined the climate — with a cool spring, hot dry summer and low frost risk — checked all their boxes for growing their favorite wine, Tempranillo, in the U.S.

“The next thing to do was learn how to farm it,” Joll said. “If there’s anything to take away, it wouldn’t have been possible without passion and grit and scientific rigor.”

On sunny Snipes Mountain

In the small Snipes Mountain American Viticultrual Area in the Yakima Valley, Newhouse has been getting to know Tempranillo and a handful of its Spanish cousins in a block he planted in 2007 at the urging of a couple of customers.

He planted the block just below a rock wall on the south side of Snipes Mountain, an ancient uplift of river cobblestone that lies just west of the town of Sunnyside. Those rocks, facing the afternoon sun, generate a lot of heat each day but cool quickly at night due to the draw running down the slope.

“When Kevin Pogue did his survey and put like 1,000 temperature sensors all over the state in various locations, this one here was the hottest,” Newhouse said, referring to the Whitman College geology professor known for his work on terroir. “I just thought that, reading about what Tempranillo likes, hot days and cool nights, that this would give us this best-of-both-worlds with the draw here.”

Over the years, he’s swapped out a few Spanish port grapes — whose intended market didn’t materialize — for Mourvedre and, he said, “it’s just a dynamic, awesome site” for the variety.

The Tempranillo likes the spot, too. The 4 acres of grapes go to a handful of wineries — including Alfonso’s Idilico winery, which takes the first pick, and others that opt to let the fruit hang for a few more weeks.

Tempranillo’s vigorous tendencies provide a bit of a challenge.

“If you get a little bit too much water, you can’t shut the canopy down,” Newhouse said. “But if you don’t give it quite enough water, you end up losing a bunch of leaves on the west side of the canopy, where the afternoon sun hits.”

That’s a recipe for stress and sunburn. This year, he struck the balance spot-on, he said when Good Fruit Grower came to visit during the first pick in early September.

The harvest crew kept an eye out for bird pecks as they picked. “This is the earliest grape to ripen, so the birds like it,” Newhouse said. He pays his crew by the hour, rather than piece rate, so they work carefully and sort.

Other blocks in his 1,100 acres of vineyard are machine harvested, but for the specialty cultivars, where he’s juggling multiple small picks for different wineries, harvest must be done by hand.

Newhouse wanted to be clear that he’s happy to share what he’s learned about Tempranillo — or any of the novel, niche varieties among the 35 or so he grows — but he’s not encouraging anyone to plant it without a contract.

“I like growing it,” he said. “If people wanted more, I’d grow it.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Starting an acreage survey

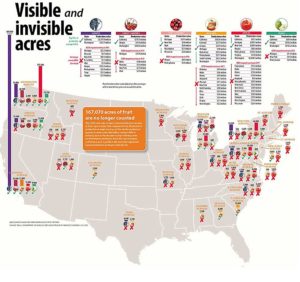

Just how many acres of Tempranillo have Washington growers planted? Or Graciano for that matter?

These are good questions, but no good data exists today to answer them. In 2017, the last time the state conducted an acreage survey, growers reported 73 acres of Tempranillo. As for Graciano, well, it’s lost in the 875 acres of other reds.

That’s why the Washington State Wine Commission and the Washington Winegrowers Association have launched an expansion to the state’s annual grape survey to ask producers more about their vineyards.

“We need to be able to talk about what’s happening in today’s market,” said Kristina Kelley, director of the Washington State Wine Commission. “Right now, our data is from 2017, and we’re talking about the 2023 harvest.”

For years, the Washington wine industry relied on acreage surveys conducted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture — typically in a cost-sharing partnership with the tree fruit industry — to provide a picture of grape acreage in the state. But the cost and lengthy timeline of such specialty surveys, along with the difficulty of getting growers to fill them out, makes it impractical to do more frequently.

“People want to know the acreage by variety. And where it is being planted, in what AVAs,” Kelley said. “It will give us a much clearer picture of the opportunities that exist in Washington state wine, particularly in light of the circumstances we are facing.”

As the Northwest wine industry grapples with an oversupply following crush cutbacks at Ste. Michelle Wine Estates, supporters of the expanded survey say it’s a critical time to have timely, detailed acreage data available.

“It’s something our industry really needs, to help us avoid situations like this,” said Todd Newhouse, co-owner of Upland Vineyards in Sunnyside and a wine commission board member. “The more data we have, the more data we can analyze to make better decisions about what to plant.”

Growers and wineries already report their annual production to the Washington State Wine Commission through an online platform, used to collect assessments and data for the annual Grape Report. This year, people will see additional questions about vineyard acreage in their profile.

“It’s just going to become part of the regular assessment program,” Kelley said. Going forward, the survey will ask growers to update the profile of their acreage, and the wine commission will crunch the data on its existing system.

The data — aggregated by AVA or by region, for some of the smallest AVAs — will then be shared with the industry early next year. Individual farm data will be confidential.

“We’re sticking to questions I don’t think anybody will have a problem answering,” Newhouse said. “It’s going to be useful to everyone, so it’s in everyone’s best interest to fill out the survey.”

—K. Prengaman

Leave A Comment