As part of his pear post-harvest gap analysis, researcher Rob Blakey jots notes after setting up equipment to measure airflow and pulp temperature in November in the conditioning room of Stemilt Growers in Wenatchee, Washington. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Some packers are better than others, but overall the pear industry is not consistently following basic standards when it comes to ripening and postharvest handling.

That’s the assessment of postharvest specialist Rob Blakey. “There is a lot of room for improvement in pear conditioning,” he said.

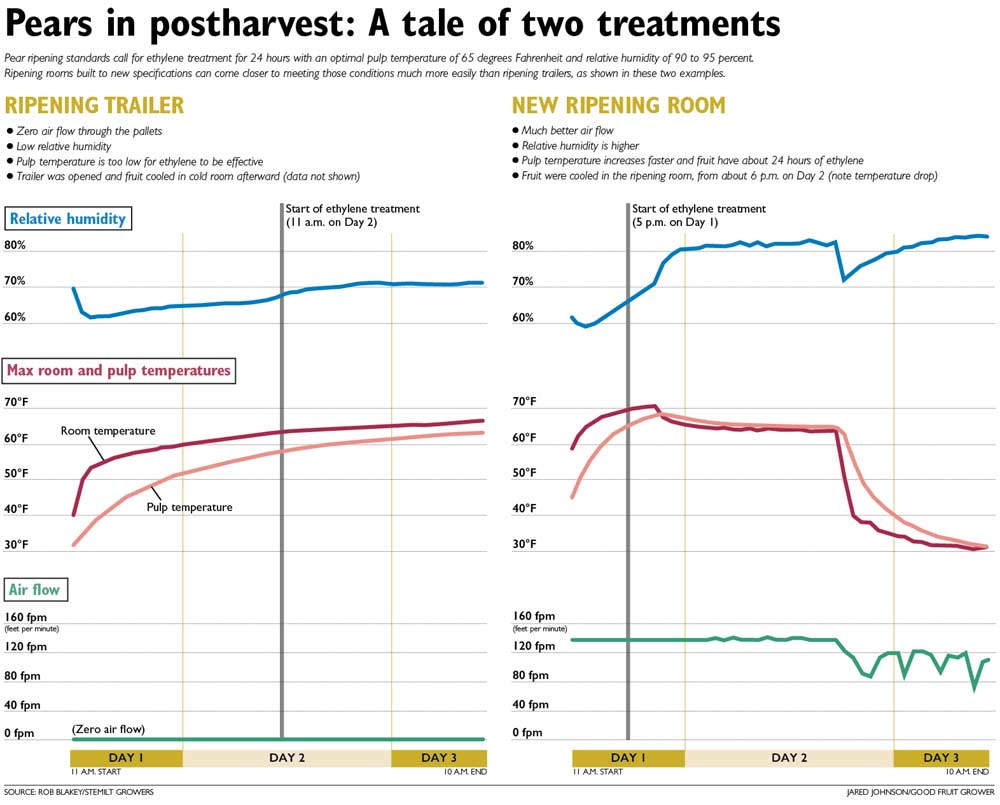

For years, Pear Bureau Northwest has published minimum pear ripening standards of 100 parts per million ethylene for 24 uninterrupted hours to pears with a pulp temperature of 60 to 70 degrees Fahrenheit — with 65 as optimal — in a room with 90 to 95 percent relative humidity.

To help everybody remember, the industry points to the acronym MATTER — maturity, airflow, temperature, time, ethylene and relative humidity.

Blakey prepares to insert a temperature probe at the base of a d’Anjou pear. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Those standards may need refining, Blakey said, but first, the industry must follow the current methods more consistently.

“What I wanted to see is are they reaching minimum standards, which the Pear Bureau recommends, and most places aren’t,” he said.

Over the fall and winter, Blakey observed postharvest pear handling techniques at four warehouses in Washington and Oregon using a $30,000 grant from the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

He plans to present his findings at the Research Commission’s pear research review on Feb. 15 in Wenatchee.

Collaborators are Dennis Kihlstadius, ripening consultant for the Pear Bureau, and Kevin Moffitt, CEO of the Pear Bureau.

Blakey performed the research as a member of the Washington State University extension faculty, a position funded in part through the $32 million tree fruit endowment. He has since left WSU and now works for Stemilt Growers, managing its research and development department.

Blakey measured air and pulp temperature, ethylene levels, carbon dioxide, oxygen and airflow in and around pear boxes. He also sampled pears with a firmness meter that probes to the pear’s core, unlike conventional penetrometers that only measure just below the skin.

Pears in postharvest: A tale of two treatments: Pear ripening standards call for ethylene treatment for 24 hours with an optimal pulp temperature of 65 degrees Fahrenheit and relative humidity of 90 to 95 percent. Ripening rooms built to new specifications can come closer to meeting those conditions much more easily than ripening trailers, as shown in these two examples. (Source: Rob Blakey/Stemilt Growers. Graphic by Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

In one warehouse ripening room, fruit with at least 60 degrees pulp temperature received ethylene treatment for only 18 hours.

At another warehouse, one that used a ripening trailer, poor airflow caused inconsistent pulp temperatures and limited the time the pears were exposed to ethylene to only 7.5 hours while they measured at least 60 degrees.

In both cases, weak ripening responses resulted and more time in a warm room with ethylene would have improved the ripening, Blakey said.

The industry supported Blakey’s work to increase demand and reduce shrink by improving consistency in delivering ripe pears, said Mike Parrish, Stemilt’s category manager for pears.

“We have gaps just in consistency, as an industry, in what we call a ripe, ready-to-eat pear,” Parrish said.

Blakey mesures airflow over a box of pears. (Ross Courtney/Good Fruit Grower)

Blakey promised the five warehouses anonymity, but Stemilt agreed to photographs and an interview with Good Fruit Grower.

Some Northwest pear packers have invested in state-of-the art conditioning rooms that have ethylene generators, sophisticated temperature controls and numerous vents to improve and even out air flow.

It would be nice if others did the same, Blakey said, but that’s only part of the problem. Packers too often try to spot condition, he said, shipping pears prematurely to meet the demands of a marketing desk, rather than make sure all the fruit follows a set conditioning program.

“A sophisticated ripening room doesn’t count for much if the fruit hasn’t had enough temperature and time, temperature and ethylene,” he said.

Pears can be successfully conditioned in a low-cost room with ethylene and a fan, if the packer is diligent about adjusting for time and temperature and follows a program in partnership with the retailers.

“So it is tricky to go into a program,” Blakey said. “It requires a lot of work. But we did it with avocados.” That’s one reason avocado demand has surged. The U.S. consumption alone went from 1.1 pounds per capita in 1989 to 7 pounds per capita in 2014, according to the Agricultural Marketing Resource Center.

Before joining Washington State University, Blakey worked in South Africa and the United Kingdom researching postharvest handling of avocados. •

by Ross Courtney

Hi ross,

can you share the effects of post havest management?

Thanks