Washington growers founded the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission in 1969 with a goal of developing an automated harvester, but the vision and engineering technologies necessary for such an endeavor never quite kept pace with the needs of the tree fruit industry.

Until now, perhaps. The robotic harvester under development by Abundant Robotics (read and watch “The long and tricky path to automated picking”) is able to remove apples (and pears) quickly without inflicting damage in the process. The machine is being programmed to recognize fruit size and color and to “see” fruit and pick it as the machine moves down the row.

The high potential for success means it may be time to contemplate the current and future opportunities to further automate the apple and pear industries and to begin identifying synergistic technologies or developments — such as mechanical pruning, 10-foot minimum width drive rows, the handling properties of specific varieties and the growth habits of trees.

Horticultural challenges

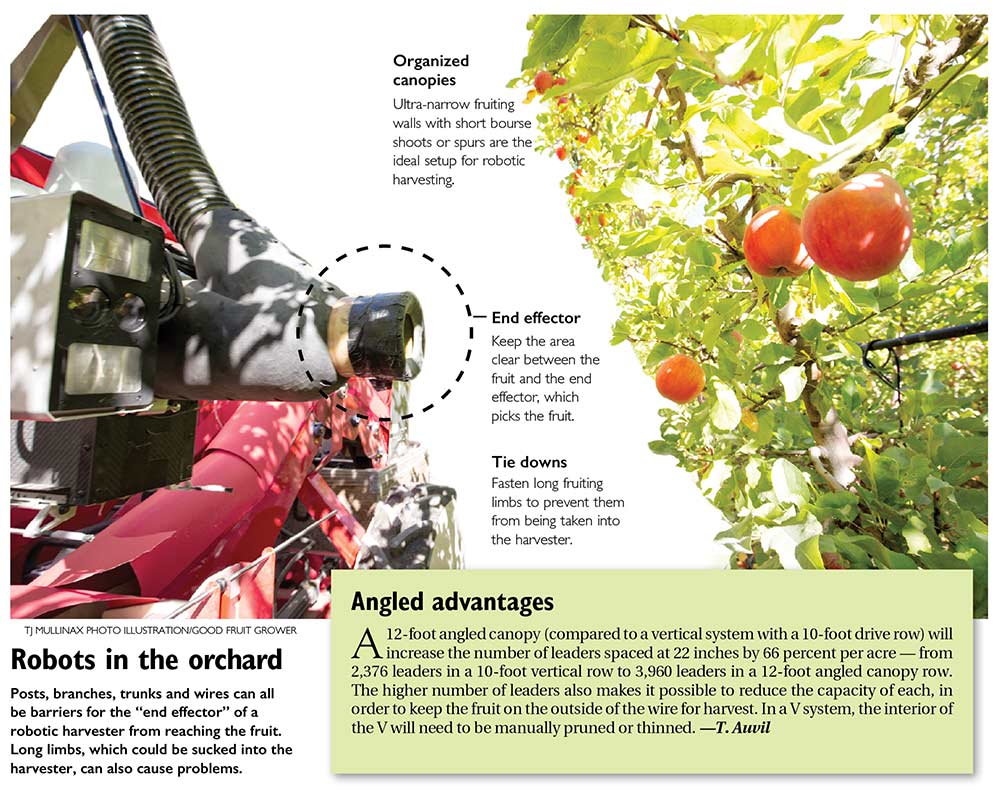

For best results with the current version of the technology, there should be nothing between the “end effector” and the fruit; posts, tree limbs, trunks and wires all can be barriers to reach the fruit. In addition, long limbs can be sucked into the end effector, bruising and cutting the fruit that subsequently enters and passes alongside it.

To prevent damaged fruit, growers should fasten those fruiting limbs (greater than 9 inches long, greater than 10 mm in diameter or 3/8-inch caliper) to prevent them from being taken into the harvester.

Very organized canopies, where all fruiting wood is fastened to wires (or is composed of very short bourse shoots or spurs) should be compatible with robotic harvesting, regardless of whether they are vertical or angled canopies.

The very narrow canopy provides much more uniform solar radiation (heat on fruit), light distribution and fruit distribution. A much higher portion of fruit can be ready for first pick in well balanced, ultra-narrow fruiting walls.

However, random training, where only the more vertical leader is fastened to wire, is more challenging. In addition, for the robotic harvester to have the best access to fruit, wires may need to be outside the posts and the trees outside the wires, contrary to how angle canopy blocks have evolved in recent years.

Mechanical pruning appears to be a very quick and consistent method of minimizing problem wood protruding into the drive row. In the longer perspective, if the harvester can fit into 10-foot centers (plus or minus 1 to 2 feet, to be able to efficiently work in rows with variable widths of 8 to 12 feet), then vertical systems could be considered to utilize mechanical pruning, thinning and harvesting technologies.

Future synergies

The spatial distribution of limbs and fruit in this Gala block at Wafler Farms in New York, designed by Paul Wafler, allows all the apples to be “seen” by a camera/robotic harvester. In addition, the light distribution allows for even color and maturity development of the fruit. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

If a robotic harvester with bin filling can function in older 10-foot centers, the opportunity to nearly fully automate the apple and pear industries is at hand.

That may require planting systems that utilize two- or three-leader trees spaced at 18 to 30 inches between vertical leaders depending mostly on the vigor/growth habit of the scion; more vigorous, tip-bearing varieties will require more space.

Two leaders per tree at 18 inches between leaders will place stumps 3 feet apart; three leaders at 26 inches will place stumps 6.5 feet apart.

One key to remember: As the distance between leaders increases and the number of leaders per stump increases, the development of a uniform canopy can become increasingly difficult.

These mechanically intensive systems will economically perform best when production canopies achieve uniform height and width.

As the number of leaders per stump and the distance between leaders increases, additional management is required to grow consistent canopies.

(“Management” may be defined as deploying tactics to weaken strong leaders and increase vigor of weak limbs by changing the angle of the leader, defruiting the weak leaders, and perhaps lightly girdling strong leaders to increase fruit set and reduce vigor.)

In New York, Wafler Farms has a production system that has reduced the number of horizontal wires in the angled canopy production system.

The fruiting limbs have been ideally distributed along the drive row (mechanically pruned on two sides of the V) to allow every apple to be visible from nearly every possible position.

This not only allows the harvester vision system to see a very high percentage of fruit, it also allows uniform color and maturity of the crop, enhancing the productivity of the autonomous harvester developed by Wafler.

The vertical leader of each tree is supported by a wire. Other options in the vertical support include bamboo or fiberglass rod. Wafler wraps the leader of the tree around the support wire, and by the time the tree passes the top horizontal trellis wire, the tree has been lightly girdled by growing around the vertical support wire.

A Gala block visited during the International Fruit Tree Association tour last summer was a marvel of consistent vigor, consistent crop load and very consistent canopy.

This third-leaf Cripps Pink block — with three leaders per rootstock trained vertically over three horizontal wires, guided by string — has fruiting sites all along the vertical leaders. This crop was expected to exceed 60 bins per acre. (Courtesy Tom Auvil)

The multileader format appears to be very simple to train and support.

The critical factor in developing the multileader is uniform spacing of the leaders; if the leaders are not uniformly spaced, they will eventually shade each other out. In addition, the horizontally trained systems need manipulation as each “vertical” leader crosses the horizontal wire to induce at least two branches every 18 inches, tied horizontally in two or more locations to minimize environmental effects.

The tools available to mechanically prune and adjust pruning have evolved considerably in the past five years, as have the abilities to plant the very straight rows that will enhance machine performance.

The next era in tree fruit harvest is upon us. •

Planting the next orchard

When deciding how to plant your next orchard, there are a number of questions to be considered.The first: What is your planning horizon, five years or 20? If the answer is 20 years, you may need to consider ground and overhead crop covers to maximize revenue and limit cullage. Exclusion netting to minimize outside sources of stink bug and codling moth may be an integral decision, and that system should be planned the day the orchard is laid out on paper to reduce costs.

The next decision is the type of system: formal, horizontal wire training or multileader upright. The formal system begs for bench grafts or sleeping eye nursery stock so there is no crop or bloom to interfere with the high vigor needed to induce branching where needed. Substantial investment in labor is needed to induce branching and securing the branches to horizontal wires.

Multileader systems can also benefit from bench grafts, sleeping eyes or small (less than 1/2-inch caliper) whips to be headed below the knee at planting. Developing and maintaining uniform spacing of the leaders is the challenge.

Either string, bamboo, or fiberglass rods can be used to support and maintain the precise spacing of the leaders. In the second leaf, some work may help develop very uniform distribution of fruiting wood. Light girdling every 10 inches of each leader followed by four weekly maximum label rate 6-BA (Promalin) applications will help the bud break up and down each vertical leader.

– by Tom Auvil, research horticulturist for the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

Leave A Comment