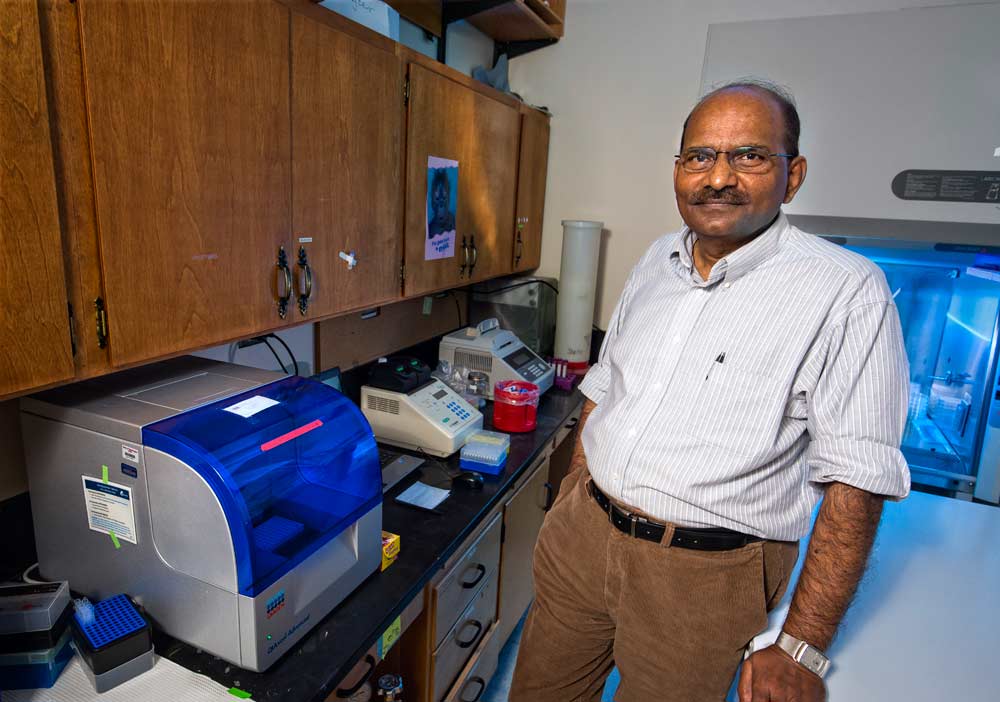

Naidu Rayapati stands with a QIAxcel Advanced DNA and RNA electrophoresis machine that helps his team significantly reduce plant sample test times at Washington State University’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center, in Prosser, Washington, in January 2018. Rayapati, who is an associate professor and plant pathologist at WSU, says with the machine he can process gene samples in two days compared to a much longer process using traditional gel analysis. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

For so long, Washington State University plant pathologist Naidu Rayapati has been touting the importance of planting certified clean material to ward off grapevine viruses, the message may sound like it’s on repeat to growers.

And yet, it’s a message that continually needs to be drilled home, given the increasing prevalence of viruses in Washington and the challenges they pose: Every cultivar presents symptoms differently for each virus, if there are symptoms at all, and often symptoms for a specific virus can mimic other problems, such as mechanical injury or a nutrient deficiency.

Coordinator Teja Natria, a post-doctoral researcher at WSU’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser, Washington, strips the bark away to reveal the phloem from Merlot canes for testing for red blotch and leafroll viruses on January 16, 2018. (Shannon Dininny/Good Fruit Grower)

That’s why Rayapati is working to better understand how pervasive viruses are in Washington vineyards by employing polymerase chain reaction or PCR-based detection technologies, where a targeted area of the pathogen’s genome is copied and amplified exponentially, both to identify grapevine viruses and to assess their genetic diversity. He also employs next generation sequencing technologies to embolden efforts profiling viruses lurking in planting materials and vineyards.

Through these efforts, he aims to develop assays that can quickly diagnose a particular virus, enabling growers to answer the question of whether their plants are infected, regardless of whether the vines are showing symptoms, and, if so, if that means there are likely vectors in the area requiring some pest control.

The nearly $250,000 research project, funded through the U.S. Department of Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant program with additional funding from the Washington State Wine Commission and Washington State Department of Agriculture, continues to 2019.

How big is the problem?

Washington is the nation’s second-largest producer of premium wine, with more than 900 wineries and 55,000 acres planted in wine grapes. Though that is a fraction of the 600,000-plus acre industry in California, Washington’s industry continues to plant hundreds of new acres each year. In addition, the first generation of vineyards in Washington, planted in the 1960s and 1970s, are beginning to require replanting, either due to age or disease or to replace with a more popular cultivar. Ste. Michelle Wine Estates, the largest player in the state, has estimated it will need to replace 5 percent of its acreage each year — a move that requires 1.75 million vines for the company alone. That doesn’t include vines needed for expansion.

Technician Lakshmi Movva prepares to grind cane samples to test them for red blotch and leafroll viruses at WSU’s IAREC in Prosser, Washington, Jan. 16, 2018. (Shannon Dininny/Good Fruit Grower)

As a result, more and more growers are turning to field grafting to start new blocks. If done properly, field grafting can get a vineyard back into full production within three years, compared with four or five years in a replant situation. However, field grafting also raises the risk for disease to be transmitted either from an infected trunk to the new scion or vice versa — or worse, for both to be infected, but with two different viruses that then spread through the vineyard.

Part of the grant money is being used to improve sampling strategies, Rayapati said, to encourage growers to at least test a percentage of vines from existing blocks where they would like to graft, as well as the graft wood. “Both the scion wood and the existing trunk have to be clean. Otherwise it becomes worthless,” he said.

Of particular concern are existing vineyards with white wine varietals, which typically don’t display virus symptoms; for example, many growers are cutting back Riesling blocks to graft red varietals, such as Cabernet Sauvignon, without first testing to ensure both are free of viral pathogens.

The drawback

Cost is the primary factor discouraging growers from testing, Rayapati said, but his team has also come up with new strategies to reduce that burden.

If a grower takes 100 samples to a commercial lab for testing, they will be charged $20 for each virus tested, per sample. So, if the grower wanted to test a sample for both red blotch and leafroll virus, the cost would be $40.

“Instead of testing each sample for two different viruses in separate assays, we can test for these two viruses simultaneously in the same assay — without compromising the specificity and sensitivity. We have the technology,” he said. “That’s one of the advantages, so we can ensure growers that we can provide these kinds of services in a cost-effective manner and encourage them to embrace these new technologies for their benefit.”

The researchers use either dormant canes or a leaf sample for testing. However, either one requires destructive sampling. Developing nondestructive methods for detecting a sick vine early is very important, especially for nurseries, he said.

That’s why researchers also are continuing to develop sensing technologies that could more quickly detect the virus in the vineyard, either by recognizing volatiles released by the sick plant or by recognizing distinct spectral characteristics of leaves that can be seen on the infrared visual spectrum.

“Most of the time, the symptoms are expressed late in the season, not in the spring, whether it’s a red grape or white grape cultivar. Sometimes that can be too late for management purposes,” he said. “Using these technologies, we may be able to come up with some strategies for early detection of sick vines.”

And not just detection, but also management — what is working, what isn’t, and how best to strengthen the grapevine plant material supply chain benefiting the industry, he said.

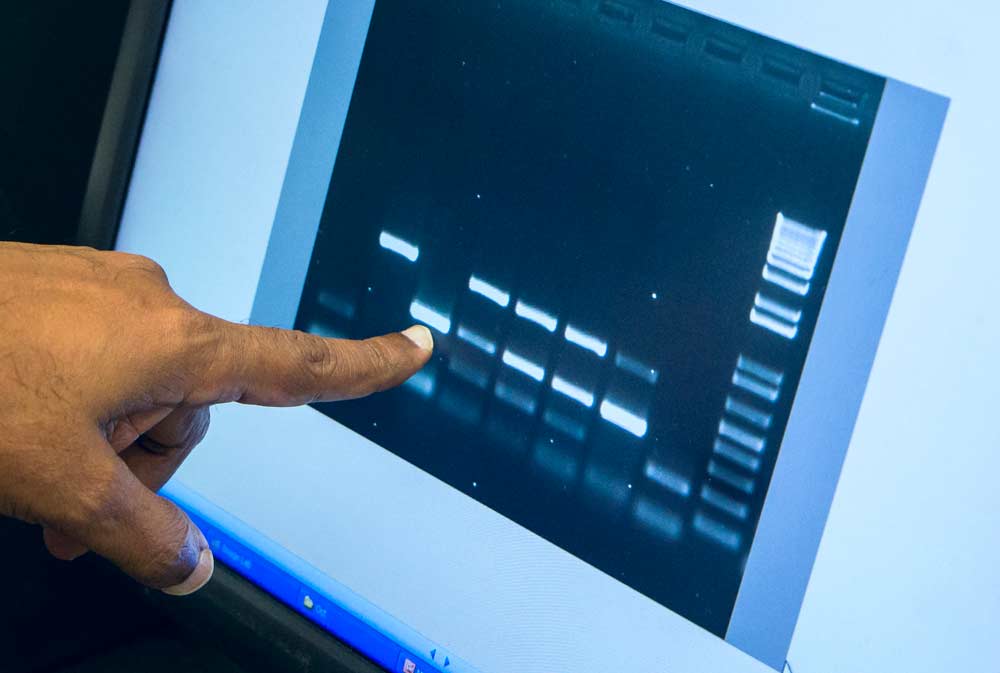

The results of this assay show samples that were positive for either red blotch or leafroll 3 virus. Each bar represents amplified DNA from that sample. The bright dashes on the top band across the screen reflect positive test results for one virus, with the bottom band showing positive results for the other. Two samples were positive for both viruses. (Shannon Dininny/Good Fruit Grower)

To that end, Rayapati is planning a series of workshops to show growers firsthand the variations under field conditions of viral symptoms versus other conditions, such as damage caused by feeding mites or mechanical injury or a nutrient deficiency. The goal is to draw more growers to participate in a bottom-up approach and to train field workers, too, in how to spot symptoms and vectors and manage diseases. He also would like to organize more grower meetings in different regions across the state, whereby neighboring growers share information about what they’re observing and how they’re dealing with problems.

“Because a problem in one area affects everyone,” he said. “If we can build community-based approaches to learn from each other and work together, we can better fight viral diseases and protect the industry from these pathogens.” •

—by Shannon Dininny

Leave A Comment