The first step to precision vineyard management is automated analysis such as using proximal sensing technology to assess canopy vigor, as these University of California, Davis researchers did in a table grape vineyard in Delano, California. (Courtesy of Kaan Kurtural)

Driven by deepening labor shortages, wine grape growers across the country have been increasingly embracing mechanization for a growing number of vineyard tasks, and now they’re taking automation to another level: precision analysis tools to track vigor, predict production and spot struggling vines early.

Interest is high — whether it’s from big farms or small, from expansive vineyards seeking efficiencies to produce value wines or from premium plantings that aim for perfection — but just like mechanized management, these emerging tools need to be proven, said Kaan Kurtural, extension viticulturist at the University of California, Davis.

As the manager of the university’s Oakville Station research vineyards, he’s testing many of these tools in a “no-touch” vineyard, guided by sensing technology and managed by machines.

That’s the inevitable future of vineyard management, Kurtural and others say.

“Initially, our goal was to mechanize to save costs, but we’ve noticed that the quality of the fruit is vastly superior,” Kurtural told Good Fruit Grower.

As an example, he cited the efficient water use in an exposed canopy of mechanically managed Cabernet Sauvignon grapes.

“We’re finding more consistent yielding with better fruit quality.”

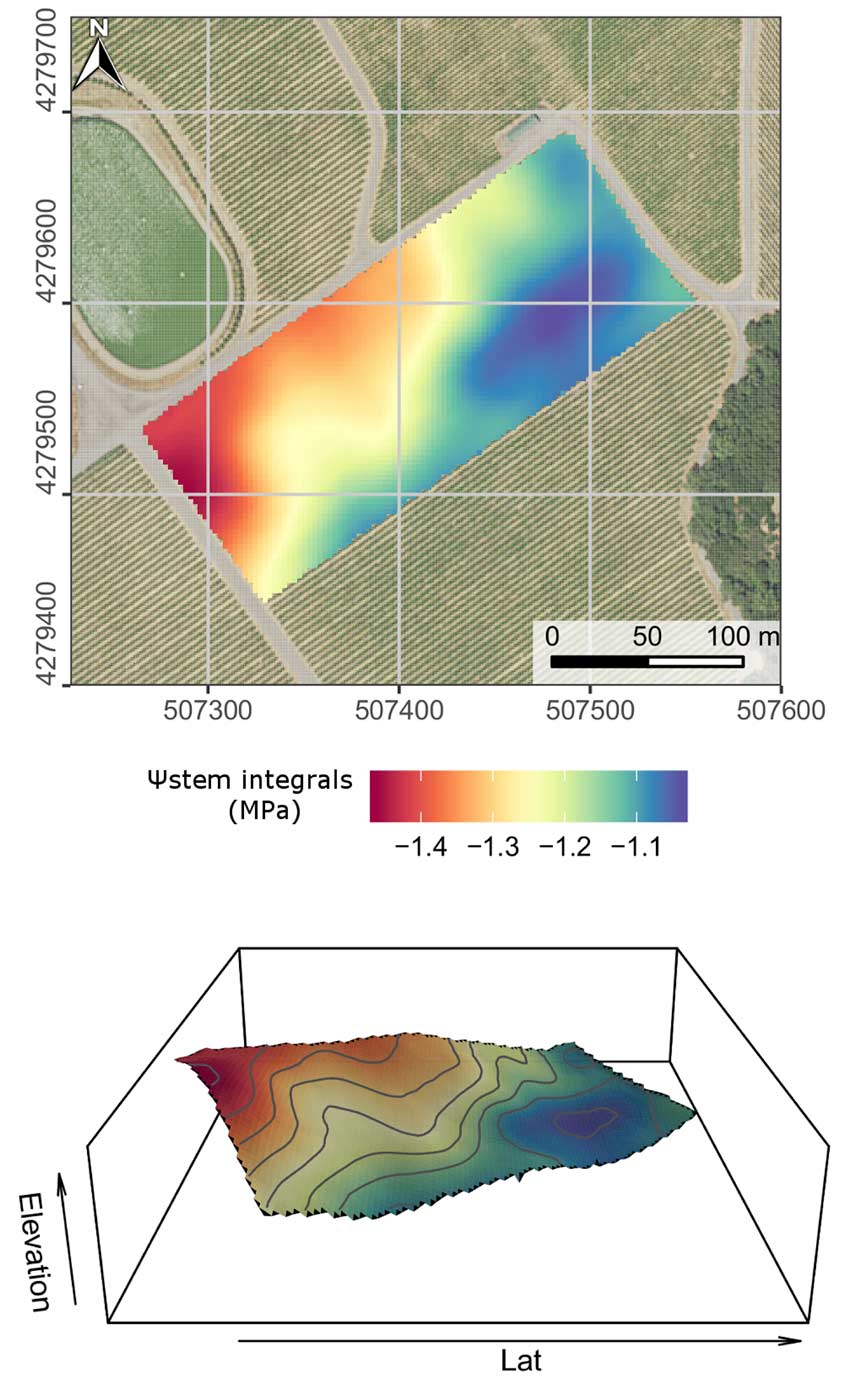

This map shows stem water potential, which is used to determine vines’ seasonal water stress, in a Sonoma, California, wine grape vineyard. (Courtesy Kaan Kurtural)

Studies like Kurtural’s and many others convince wine makers to welcome fruit from mechanized vineyards, but for growers, it still takes a push to take a leap of faith into more aggressive mechanized management, said Richard Hoff, viticulturist for Mercer Canyons, located in Washington’s Horse Heaven Hills region overlooking the Columbia River.

The nearly 2,000 acres he manages are some of the most highly mechanized in the state, he said, and he still gets nervous about it.

“It’s a big unknown, and a lot of people are afraid to make the leap,” Hoff said of mechanizing tasks like pruning. But a lack of skilled labor for Mercer Canyon’s expanding vineyards left little choice. “The impetus for us was just the challenge to eliminate tasks that require people.”

While expansion may be driving mechanization for Washington growers like Hoff, grape acreage is on the decline in parts of California, like the San Joaquin Valley.

Known for big vineyards that supply grapes for value wine, the valley has lost thousands of acres in recent years due to increasing competition for land, water and labor, according to Keith Striegler, grower outreach specialist at E. & J. Gallo Winery, who participated in a panel on mechanization at the Washington Wine Growers annual conference in February.

Increased efficiency through mechanization and improved management of vineyard variability are needed to keep growers in business, he said.

Moving toward a no-touch vineyard?

A majority of wine grape acreage in the western U.S. and in New York is now mechanically harvested, but the adoption of other mechanical management practices differs dramatically, depending on variety, existing training systems, vineyard size and, of course, growers’ willingness to make big changes.

In California, leaf removal is done mechanically on 55 percent of the acreage, and almost 20 percent is now mechanically pruned as well, Kurtural said. The numbers are growing every year.

Apart from mechanized cluster thinning, “the technology is there,” Kurtural said. And it’s proving economical: at $200 an acre, mechanical pruning costs three times less than doing it by hand, he said.

“So people are adapting very rapidly,” he said, including the premium production acreage in Napa Valley. “These guys are changing the whole industry. There is no question that mechanically managed fruit is resulting in better fruit for wineries in California.”

But mechanizing higher-tier blocks is harder, Hoff said, especially when you are talking about mechanized pruning, canopy control and fruit thinning, as he does on much of Mercer Canyon’s acreage. That’s because of the risk inherent in aggressive use of pruners and fruit thinners when you are shooting for just 2 or 3 tons per acre production. But he said he’s happy with what he’s seen so far this year on his premium blocks.

“Precision pruning is the backbone of our program; with it you can do everything else better,” Hoff said.

However, he’s still seeking tools to automate vineyard scouting, such as soil moisture and canopy water stress analysis, as well as estimate crop load.

“Automating crop estimation would be huge, especially for what I’m doing,” Hoff said, adding that mechanical crop thinning makes it hard to estimate crop load through cluster counts alone, due to the resulting lack of cluster uniformity. “And I’d like to automate our irrigation decision making. Now, we make decisions based on boots on the ground … so that’s a lot of upper management labor. Their time and my time could be well spent elsewhere if we could automate that part.”

Toward a precision future

Automated vineyards offer growers another advantage: the chance to fine-tune management in different parts of a block or even down to the individual vine level. That’s the goal of one of Kurtural’s new research projects, working with California wine, table and juice grape growers to determine how best to use analytics to inform or even automate adaptive management decisions.

“The idea came from riding harvesters. When we were doing these mechanization experiments, we noticed that some parts of the vineyard were underperforming and some parts are overperforming. We said, ‘If we can measure this, we can manage it,’” Kurtural said.

That measurement starts with yield monitors on the harvesters to produce spatial crop load data that can be correlated with other factors, such as soil type and canopy vigor. Once growers identify problem areas, they can irrigate more in underperforming areas or remove shoots in overly vigorous areas to create a more uniform vineyard, Kurtural said.

Studies have shown that yields can vary by 30 to 40 percent in most big California vineyards, so there is a high demand for precision management tools. The challenge, Kurtural said, is that many of the imaging services now offered to growers don’t really provide useful data.

“Most of what service providers are delivering to growers are colorful maps that don’t have the underlying detail,” he said. “There has to be spatial detail to deliver corrective action, but without the underlying data, they are just pretty maps to look at.”

Solving that problem is one of the primary goals of the $6 million Efficient Vineyard Project, funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Research Initiative. Led by Cornell viticulturist Terry Bates, researchers across the country are testing precision crop mapping tools, which measure water stress, vine health and crop load, across the country for the next three years.

For now, Kurtural recommends growers interested in taking the precision approach start with soil mapping and yield monitoring services in conjunction with a harvester. There’s no point in investing further in these tools if vineyards are already performing in a uniform way, he said.

“The goal of the project is to optimize the field. It’s driven by economics because the industry has to be really competitive,” Kurtural said. “We’re losing growers to nut trees.” •

– by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment