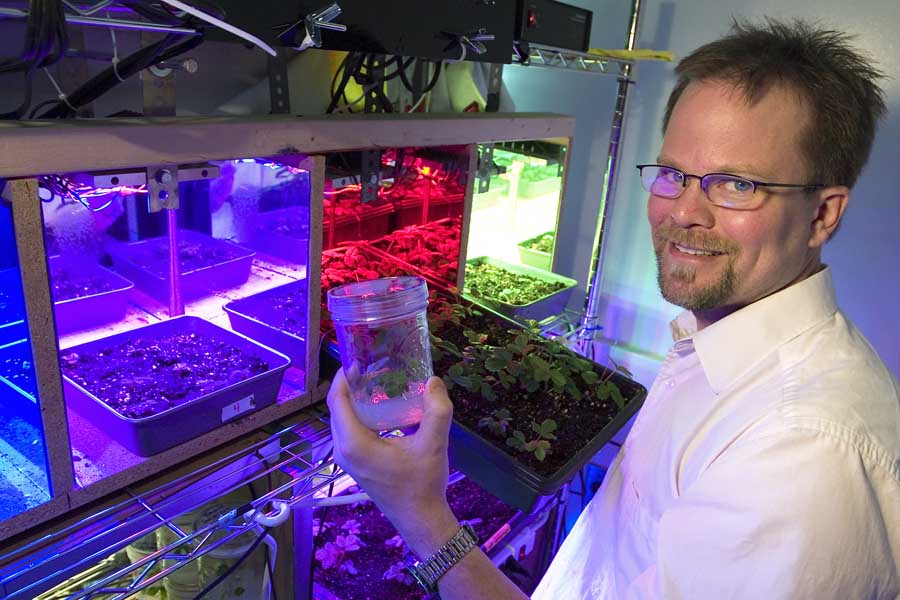

Growers need to begin engaging with consumers to counter the many online and television sources of misinformation about today’s agricultural practices, according to Kevin Folta, professor and chair of the Horticultural Sciences Department at the University of Florida. He will present his tips during a keynote address at the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Market Expo on Dec. 6-8 in Grand Rapids, Michigan.(Courtesy Tyler Jones/UF IFAS Communications)

There’s a right way and a wrong way to answer consumer questions about genetically modified foods, sprays and other agricultural practices, and growers have been doing it wrong for far too long.

That’s the position of Kevin Folta, molecular biologist, professor and chair of the Horticultural Sciences Department at the University of Florida, who will deliver the keynote address at the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Market Expo on Dec. 6-8 in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

“Whether we’re scientists or farmers, it’s very simple in our minds, because we know the products we use are safe and are very comfortable with them. The problem is that when we talk to the public about these things, we can come off as arrogant or defensive,” he said. “To a consumer, we can sound like this: ‘We know how to do what we do, and you don’t. What’s wrong with you that you don’t get that?’ We need to fix that, and it’s actually not too hard.”

A real food fight

Folta became all too familiar with this gap in communication more than a decade ago when he tried to teach the people in a favorite neighborhood organic grocery store about the benefits of genetically modified crops, or GMOs.

“I liked the people there but they had the science all wrong, and I thought this would be a great opportunity for me to share what I knew and help them to understand what’s true and what’s not,” he said. “So I went in and I buried them in data, and it didn’t change anybody. Not only that, but I went on screwing it up for 10 more years!”

It was only about four years ago that the light began to dawn, and he figured out how to get the information out there in a way that people who are not scientists or growers can appreciate. “It’s not about the data, and it’s not about the facts. It’s about how people trust and feel about their food, and that’s where we can make a difference in how we talk about ag practices,” Folta said.

First off, it’s important to understand consumers’ worries.

“Consumers are concerned about all kinds of things relating to food production, including genetic engineering; the application of herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, hormones, and antibiotics; water use; fertilizer use; land use; labor. And their opinions can be very strong.” Regrettably, he said, they are often basing those concerns and opinions on suspect sources.

“The conversation currently is dominated by people like Dr. Oz and TV chefs, rather than by the experts who actually know what they’re doing in terms of food production,” Folta said. He also pointed to “very deliberate and intentional misinformation put online by people who want to change the way we eat and the way we farm.” Some are politically driven, others are anti-corporate, but regardless of their motivation, he said, “these sources can be very compelling to consumers because it’s about what they feed their families.”

With such an inundation of misinformation, he said, the time has never been better for growers to begin speaking up.

Talking to customers

In speaking with customers, growers should lead with ethics and values, Folta said.

“Farmers have to start by talking about what’s important to them: their families, their land, the quality of their products, and why they do what they do. If people are interested in where food comes from, tell them. That’s how we can change public perceptions.”

He gave the example of pesticide usage.

“Here, a farmer might say, ‘It’s most important for me to minimize the amount of chemicals I use, because they’re expensive, it costs us money to apply them, plus I want to keep them out of my environment. And I always have to use them very carefully within the limits so I know my fruits or vegetables will be safe to eat,’” Folta said. “That’s a perfectly solid case that communicates to a skeptical consumer that the grower is concerned about the environment and consumer safety.”

For older customers who recall some issues with agricultural chemicals from the mid-20th century, he said, growers can explain how the understanding of chemistry and its impacts on the environment have greatly expanded since then, as have the regulations of the approved sprays.

“Growers can tell the consumer that today’s chemicals are targeted, they’re specific, and we know how to use them safely. We are always learning and adjusting, so what we use today is tremendously safe compared to products years ago,” Folta said.

From there, he said, the grower may want to address genetically modified foods by describing it as a way to add a trait that isn’t present naturally, and by so doing, reduce the need for insecticides to even lower levels.

Examples include the addition of a trait to papayas that essentially saved that fruit from devastation due to an aphid-borne virus, or a genetic modification to eggplants that allowed farmers in Bangladesh to vastly reduce pesticide use, realize a profit on the crop and share their seeds.

“These are all great success stories of GM technology,” he said.

The examples and the wording will vary based on the conversation, but the important thing to remember is to make a connection with the consumer first by leading with ethics and values, and then provide the evidence to support the agricultural practice, he said. This can happen in face-to-face exchanges or on social media.

“The difficult person probably won’t be influenced by the farmer, but other passerby readers will,” he said.

“They will appreciate the grower who is extending compassion and expertise, and that will help them make up their minds.“Our individual farmers have the power to fix these misconceptions, and should become comfortable operating as reputable sources, whether that’s in person or on social media,” he said. “This is how we’ll make a difference and take back this conversation.” •

– by Leslie Mertz, Ph.D., a freelance writer based in Gaylord, Michigan.

Leave A Comment