“Continuous Change,” the theme of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association 112th Annual Meeting, is a familiar challenge to the Washington tree fruit industry.

Every year in its 112-year history, this meeting seems to confront a “new normal.” What may be distinctive now, however, is the pace of that change — the scary rapidity with which the new normal becomes old. Everything about the tree fruit industry now moves at an accelerated pace. Globalization and the digital revolution have been catalytic in this phase shift.

Every once in a while, though, the continuity of change is disrupted significantly.

For example, look back at the hugely disruptive impact of genuinely transformational technologies: federal irrigation projects, dwarfing rootstocks and high-density systems, new scion cultivars, PVC pipe, integrated pest management and biocontrol, plant growth regulators, field packing into bins, controlled atmosphere and 1-methylcyclopropene, high throughput optical sorting and so on.

The success of our tree fruit industry owes much to these innovations, both hugely disruptive and hugely positive.

Certainly, it is easy enough to look backward, identifying and tracking such disruptions, from initial introduction through extensive adoption. One excellent source for that retrospective examination is the proceedings of our annual meetings.

However, when these technologies were actually new, it was not at all clear whether they were winners or losers, game-changers or hype. This meeting in 2016 should help answer that tough, and often very expensive, question.

Several sessions will feature exciting presentations on potentially disruptive technologies that will help our industry deal with challenges like consumer expectations, food safety, maximizing revenues, and transitioning to the next generation of growers.

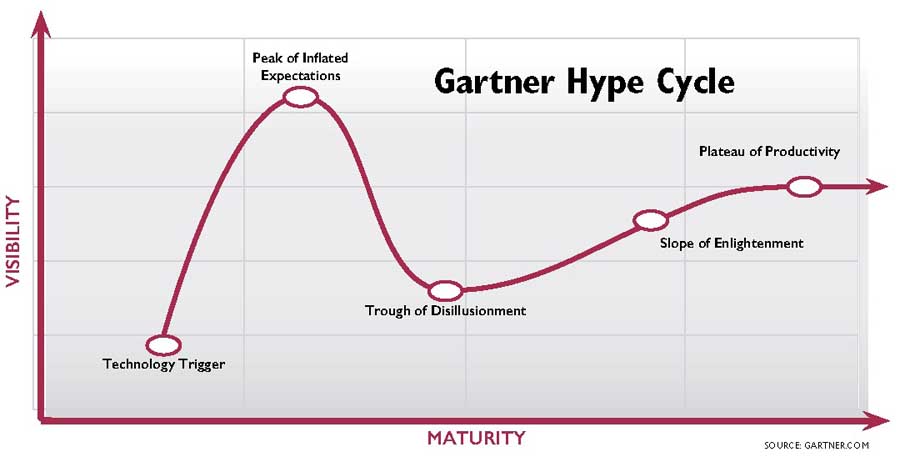

Now the question becomes: “Which of these technologies should I be incorporating into my tree fruit operation, and when?” A useful approach to assessing the risk of investing in a given technology or application uses the Gartner Hype Cycle (www.gartner.com/technology/research/methodologies/hype-cycle.jsp), which identities the five key phases of a technology’s life cycle (see graphic).

This chart identities the five key phases of a new technology’s life cycle and can be used to assess the risk of investing in the technology. (Source: gartner.com)

The cost: The benefit of early adoption versus a wait-and-see approach is exceptionally difficult to predict, but those decisions based on solid, science-based information can help separate real drivers from hype.

That is exactly what many of the presentations in the WSTFA annual meeting seek to do, providing solid, relevant examinations of potentially disruptive technologies like a prototype robotic harvester, commercialization status of the new Washington State University apple cultivar known as Cosmic Crisp, new rootstocks, trellis engineering, solid-set canopy spraying, overhead netting, optimizing water use, the WSU Decision Aid System, and decision support systems for crop protection and crop load management.

The technologies central to many of these presentations can be traced to the National Tree Fruit Technology Road map, the subject of the 37th Batjer Address.

The road map, emerging out of the turbulent economic times of the late 1990s, was a collaborative effort of industry stakeholders and the U.S. research and extension community.

It was an explicit and pioneering effort to develop a proactive strategy to enhance the profitability and sustainability of our national tree fruit industries in the face of globalized trade and technology.

Road map participants believed future markets for our products would be consumer-driven and quality-oriented, with production increasingly distributed worldwide.

Further, the road map asserted the very technologies driving this shifting market are the ones that would empower our agricultural producers to compete successfully. It was an attempt to define our future rather than simply react as it zoomed toward us, developing and adopting new technologies at the speed of the real word.

While aspirational, it was also oriented toward outcomes of real world significance.

The road map also featured a novel public-private partnership. A dedicated team comprising Jim Cranney, then at USApple, Phil Baugher of Adams County Nursery, Herb Aldwinckle of Cornell University, Clark Seavert of Oregon State University and Dariusz Swietlik of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service joined Fran Pierce of Washington State University and me, then in my role as manager of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission.

Initially driven by the desperate economic situation faced by the Washington apple industry in 2000, we quickly realized the sort of approach and technological innovation we envisioned was much more broadly applicable — not only to apple producers across the country, but also to other tree fruit producers. In fact, as the effort evolved, it became clear we were involved in a disruptive activity ourselves.

Increasingly, specialty crop industries throughout the country, especially those dependent on hand labor, recognized their economic challenges were similar, and slowly terminal, unless addressed.

While technological innovation alone does not guarantee economic sustainability, without its transformational power, we argued specialty crop industries could not possibly optimize production and handling processes and consistently deliver premium quality products to our consumers.

Further, we argued for a public-private partnership with a team-oriented, systems-based approach funded via competitive programs through the USDA. We advocated that research and extension activities should address industry stakeholder priorities and seek complementary findings from industries themselves. We suggested emphasizing two scientific areas, both advancing rapidly via digital technologies:

—Genomics, genetics and plant breeding.

—Engineering solutions.

Within those two areas, we sought to develop and fund initiatives with three goals:

—Automate orchard and fruit handling operations.

—Optimize fruit quality, nutritional value and safety.

—Deliver information via digital technologies.

This all took time. The full story of the road map itself is like a sausage: The end product is a lot more interesting than the process to produce it. Endless strategic sessions in less than exhilarating hotel conference rooms. Countless rewrites of documents. Regular visits to tree fruit commodity group meetings nationwide. Travel through

Congressional and USDA National Program staff offices in Washington, D.C. And eventually, some tangible successes, such as the creation of the Specialty Crops Research Initiative and the Specialty Crops Block Grant Program.

The Tree Fruit Technology Road map had a lot to do with that, but so did similar efforts among other specialty crop industries, with crucial support from organizations like the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, Northwest Horticultural Council, USApple, and the Specialty Crop Farm Bill Alliance, as well as Congress and the USDA.

Projects like RosBREED and Comprehensive Automation for Specialty Crops were standout wins for the national tree fruit industry. Another tangible success, this one directly associated with our Washington tree fruit industry, is the WSU Tree Fruit Endowment.

This gift, the largest in WSU history, has created an amazing legacy of industry partnership with WSU’s research and extension activities supporting our tree fruit industry.

Driven by industry priorities, these investments over time will provide a world-class research and extension base that will contribute to our economic sustainability in a competitive world market and help keep our fantastic fruit and fruit products affordable, accessible and health giving.

The National Tree Fruit Technology Road map is itself a meaningful legacy. I appreciate the honor of delivering the 37th Batjer Lecture on behalf of the many industry stakeholders and research/extension professionals involved. •

Learn more about the WSTFA 112th annual meeting, visit wstfa.org/annual-meeting

– by Jim McFerson, Ph.D., the director of the Washington State University Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center.

Leave A Comment