The key to managing productive vineyards in Washington’s variable climate is to make management decisions based on the vines’ phenology, not the calendar, according to speakers on the “Farming by Phenology” panel at the Washington Winegrowers annual meeting in Kennewick.

Understanding phenology — nature’s calendar — and predicting it based on weather forecasts can improve disease and pest control and improve fruit quality.

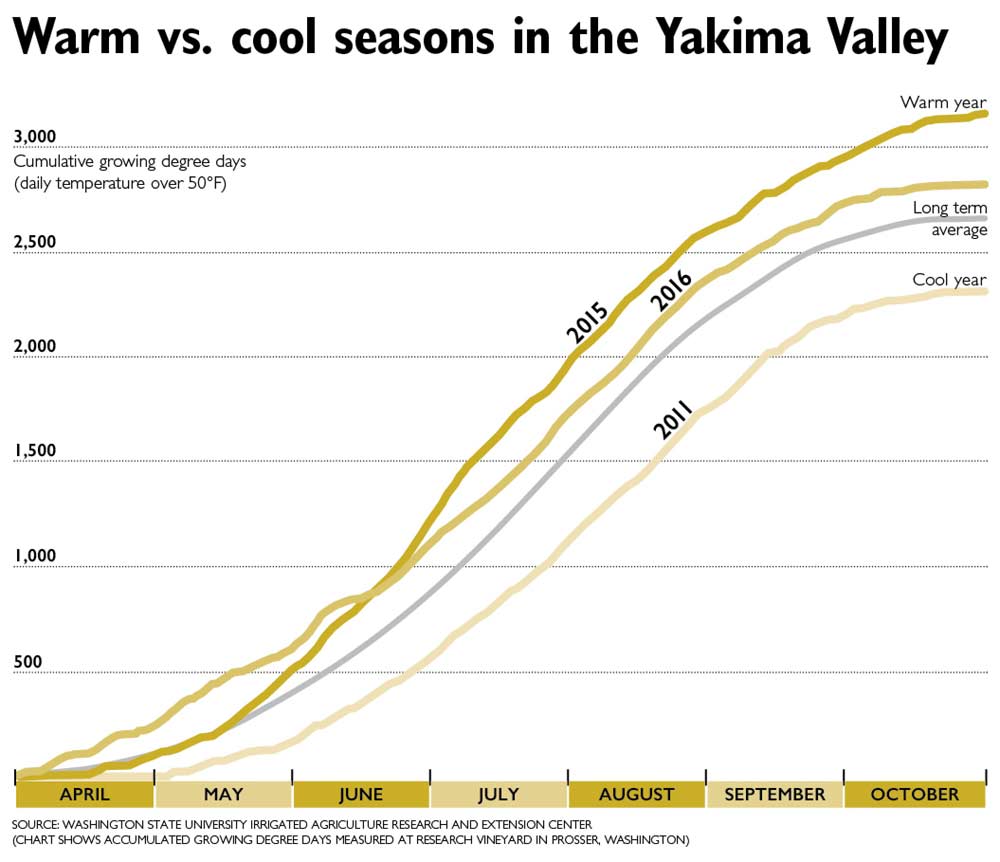

And in Eastern Washington, the difference between a warm growing season and a cool one can mean major shifts in the timing of bloom, harvest and all the vineyard labor in between.

“Your spring temperatures will determine how you manage the vineyard later on,” said Markus Keller, a Washington State University viticulturist. “Grapevines can pick up or slow down the pace depending on the prevailing temperature.”

Warm spring weather leads to rapid shoot growth and bigger flower clusters, which leads to more fruit set, Keller said. That means growers may want to use more deficit irrigation to control growth.

Conversely, in cooler seasons, growers might increase irrigation to spur growth, he added.

The difference between warm (2015) and cool (2011) years has big impacts on vineyard management, from timing of bloom and harvest to making efficient use of your workforce and controlling pests. (Chart shows accumulated growing degree days measured at research vineyard in Prosser, Washington) Source: Washington State University Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center

Many growers look at the date of bud break to assess whether it’s going to be a warmer or cooler year, Keller said, but it’s actually the accumulation of temperature that leads to veraison.

That means that growers need to keep a careful eye on this season’s weather and review data on past years to effectively plan management.

This seasonal variation is measured using the accumulation of growing degree days (daily temperature above 50 degrees) from April through October.

Washington’s Yakima Valley, for example, gets about 2,660 GDD on average, according to data compiled by WSU. But the difference between a record warm 2015 and a cool 2011 was almost 850 GDD.

“Determining if it’s a hot or cold year is something that is ongoing on a weekly basis all throughout the season,” said Jim McFerran, viticulturist at Wyckoff Farms in Grandview, Washington.

“Have diligence with recording all the major phenology events that occur through the year. It’s not just limited to bloom phase dates or lag phase dates and bunch close dates but also things related to peak ET,” McFerran said, referring to evapotranspiration rates.

In 2016 the ET hit its high point slightly early, but then it quickly dropped back down, he said.

“What I saw was a lot of acreage in the state of Washington that continued to get over-irrigated post peak ET, which led to the bigger crop that we had that was 10 to 20 percent higher than we expected,” McFerran said.

Overwatering in 2016 may have been a reaction to the 2015 heat, which kept ET high much longer than normal.

That’s why it’s best to gather real-time data on your own vineyards, with soil moisture monitors for example, than to operate based on past trends, said Kari Smasne, vineyard manager for Ste. Michelle Wine Estates.

Labor

When a warm spring turns into a hot summer, as Washington growers experienced in 2015, the entire growing season moves faster. That can test an already stretched workforce.

Warm weather means the window for accomplishing key tasks such as shoot thinning and leaf removal is condensed, but timing it right is critical to producing premium grapes, said Chris Banek, the owner of Banek Winegrower Management.

“With the skilled labor that we have available to us, it’s all about timing,” said Banek. “Once you get late, it’s really tough to catch up, especially in an early year.”

By tracking the accumulated growing degree days, you can predict bloom and therefore, approximately how much time you have to get shoot thinning done, McFerran said.

And if your labor force is limited, mechanization is another tool to help meet those deadlines.

“It’s prudent to come up with a plan B. While a mechanical shoot thinner can’t do the job 100 percent effectively, it can buy you time,” McFerran said. “For me, it all comes back to tracking, tracking, tracking and to have certain seasonal goals in mind for task accomplishment and how you are going to accomplish them by that date, and if you don’t have enough arrows in the sheath, it’s time to get more arrows.”

Smasne said that at Ste. Michelle’s Canoe Ridge vineyards, management in a hot, fast year means making more decisions about priorities.

“We try to get to our high tier blocks first, especially when labor is really hard to come by,” she said. “Then, we are as a company trying to incorporate more mechanization to help us get through these tasks in seasons that are compressed and we don’t have a lot of time.”

Pesticides by phenology

Vineyard pests and pathogens each have their own phenology as well, often tied to both climate and vine development. Understanding those relationships allows growers to predict and plan to use pesticides at peak efficacy.

But just as unexpected warm weather can strain labor, it can also create new challenges for pesticide plans.

For example, when warm spring weather boosts vine vigor, it results in a dense canopy that requires more spraying to control powdery mildew than a slower growing canopy in cool weather, said WSU viticulturist Michelle Moyer.

“Early, rapid canopy fill can be a good thing, but it’s not good if the plant can outgrow the preventive products,” she said. “It’s a problem for pesticides that have to be in contact with the tissue to work.”

Come summer, however, that warm weather allows for better canopy management through deficit irrigation, while cool weather will favor mildew and botrytis blight, she said.

“When we have these long delays in fruit ripening, either due to cool weather or too hot weather, it can really set you up for botrytis,” she said.

The takeaway from all the speakers was that grapevines and the pests and diseases that target them follow the climate conditions around them. So growers need to adapt accordingly, all season long.

“Grapevines are easily able to make up about three weeks or so of bud break delay. On the other hand, they can lose about three weeks of bud break advancement if it gets cool again,” Keller said. “2016 is a good example because we predicted that we’d be harvesting in July, or at least I did, but we were still harvesting in November.” •

– by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment